Welcome to Issue No. 23 of Prime Number:

A Journal of Distinctive Poetry & Prose

Letter from the Editors (or jump to the Table of Contents)

Dear Readers,

We’ve got a great new issue for you—Number 23 is the first issue of our THIRD YEAR—but first we want to welcome our new Book Review Editor, Heather Lee Schroeder. Heather has loads of experience with book reviews, including a stint as Books Editor of the Madison Capital Times. If you are a small press looking for reviews, or if you would like to write reviews, please be in touch with Heather via our Staff page.

Speaking of books, our Editor, Cliff Garstang, has just published his second book, a novel in stories, WHAT THE ZHANG BOYS KNOW, with Press 53. People have have been saying some very nice things about the book, and we think you should pre-order a copy right now.

In Number 23, we continue to bring you distinctive poetry and prose: short stories by Susan Lago, L. McKenna Donovan, Ryan Meany, and Joe Samuel Starnes; essays by Leslie Tucker, TT Jax, Vanessa Blakeslee, and Wendi E. Berry; craft essays by Heather Magruder and Josh Woods; poetry by Jan Bottiglieri, Devon Miller-Duggan, and David Salner; a storyboard by Emily Edwards; a review of Susan Woodring’s new novel; and a review of a poetry collection by Katrina Vandenberg.

We are currently reading submissions for the Issue 23 updates, Issue 29, and beyond. Please visit our Submit page and send us your distinctive poetry and prose. We’re looking for flash fiction and nonfiction up to 1,000 words, stories and essays up to 5,000 words (note that this is an increase from our previous limit), poems, book reviews, craft essays, short drama, ideas for interviews, and cover art that reflects the number of a particular issue (we’re looking for a “29” right now). If we’ve had to decline your submission, please forgive us and try again!

A number of readers have asked how they might comment on the work they read in the magazine. We’ll look into adding that feature in the future. In the meantime if you are moved to comment I would encourage you to send us an email (editors@primenumbermagazine.com) and we’ll pass your thoughts along to the contributors. Similarly, if you are a publisher and would like to send us ARCs for us to consider for reviews, please contact us at the above email address. We’re especially interested in reviewing new, recent, or overlooked books from small presses.

One more thing: Prime Number Magazine is published by Press 53, a terrific small press helping to keep literature alive. Please support independent presses and bookstores.

The Editors

Issue 23, July-September 2012

POETRY

Clichés about Angels or How I Decided on a New Philosophy and a New Style All in One Fell Swoop

Found in a Pile of Someone Else' Postcards: An Anti-Ekphrastic

FICTION

Swimming the Lake

Things I Would Say to Certain People

Continental Divide

Its Eyes Was Flickering

STORYBOARD

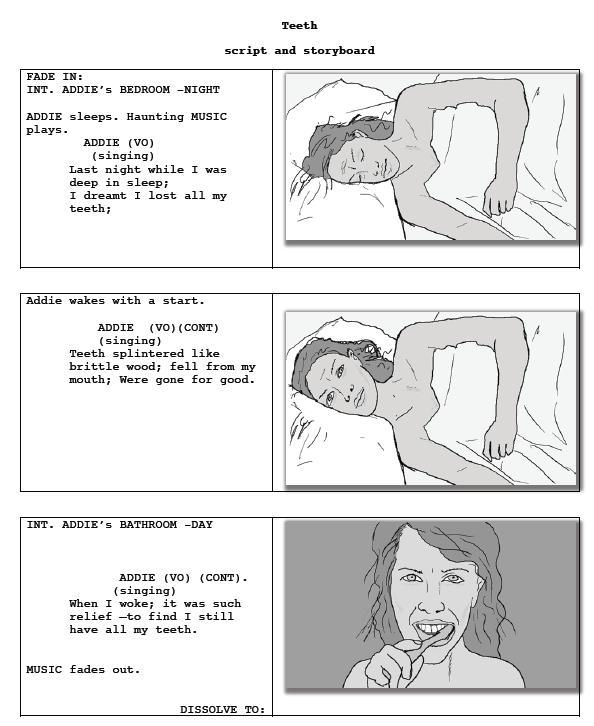

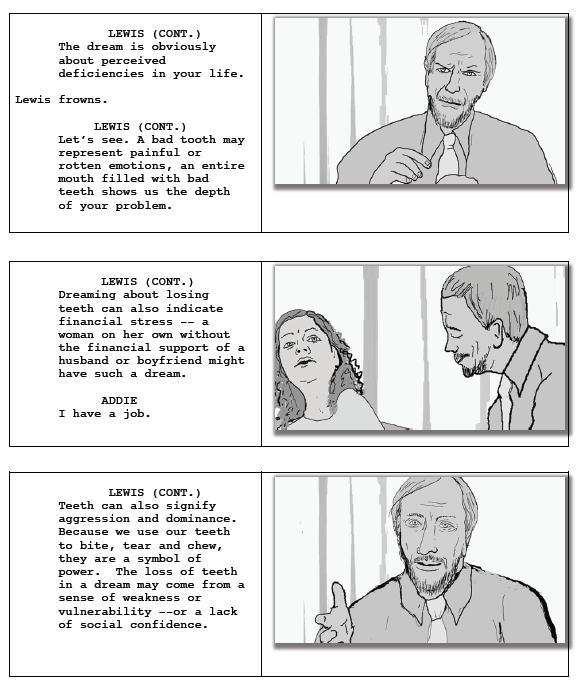

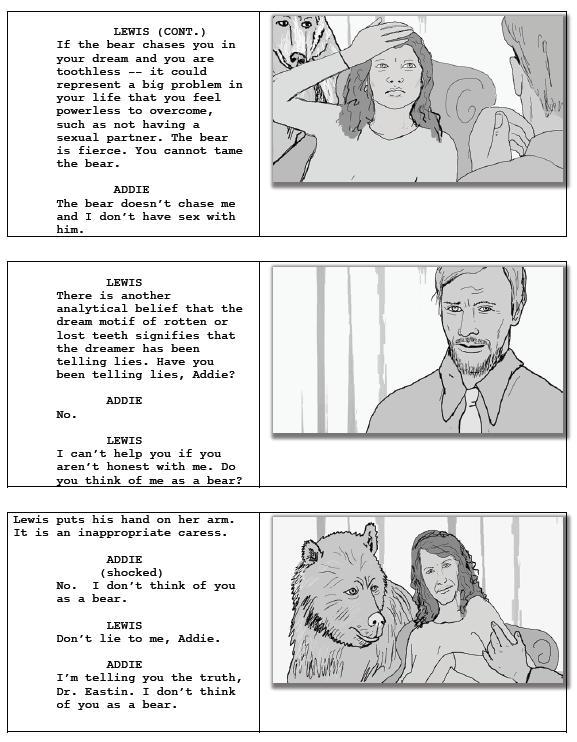

Teeth

NONFICTION

Rubber Gloves

The Lightness of Absence

Resume of an Unemployed Writer

Letting Go of Lee Smith

REVIEWS

Review of Goliath by Susan Woodring.

Review of The Alphabet Not Unlike the World by Katrina Vandenberg

CRAFT ESSAYS

A Technique for Writing the Impossible and the Unreal

The Nature of Character: Learning to Read the Natural Landscape and

Use it to Develop Characters

Poetry from Jan Bottiglieri

followed by Q&A

Nineteen

This poem

is about my boy, in the kitchen, reading to me a poem.

About my boy, nineteen, reading to me a poem from a book he has picked up

casually from my stack of books, and he flips it open and begins to read.

My boy is nineteen, and the poem on the page that falls open

is called Sixteen, and he reads it aloud to me, he is allowing me.

It is a poem about a boy. The boy in the poem, the boy in the kitchen:

they become the same, one a little grown past, the other approaching.

Grinning, my boy finishes, beautiful. And in the kitchen every thing

is so: the yellow wood, the scarlet poppies on the porcelain cups

in the cupboard behind his head, the brown shock of his head. Everything

he has just read to me, he has been to me, my boy, a poem in the kitchen.

I am praising his reading, his aloudness of Sixteen, and aloud my boy asks:

It’s about him, right? meaning the poet, and the poet is a man I know,

not a young man, and my boy thinks that Sixteen is about this man. I say,

no, it is about his son, his boy. Not him as a boy? my boy says, and I see

the wonder of this poem: it makes a boy forget he is not a man;

he reads the poem and it becomes about him, and he has become the poem.

He is part boy, part poem – the boy thinking then that he must be

an old man, or that the poet must be a boy. A poem.

This poem

is about a man – no, a boy, my boy, and we are there in the kitchen,

the scarlet shock of nineteen and the porcelain cups. I hold my boy

in the way he allows me, and I fall open, holding him.

Homunculus

Sweetiepie, Monkey,

little genius

of despair.

I know you

are in there,

pulling levers

behind my dura,

that chintzy curtain.

That’s you, rattling

at two round

windows sunk

in the bony wall;

you, flinging yourself

onto the flounced

grey bed. You practice

volition (those boring

offices) like a

creaky violin,

the same dumb scales

over and over.

When will you take

your drop of honey,

your dish of milk?

When will you

sweeten, sweeten?

You send your

susurrus down the

snakey canal:

I’ll never, I’ll never.

You are disturbing

the world’s

smallest anvil.

The Fiery Skipper

Could be wings are an affliction,/a different kind of tyranny.

— Li-Young Lee

A fiery skipper–lepidopteran,

small as a cent and colored

summer gold and bronze,

alights in the wide margin

of the book laying open

on the grass in bright sun

and first casts a scale from its wing

onto the page, where the scale becomes

the saffron dot of an invisible i;

and next closes its deepest ochre,

sorrel, sepia, between wings it holds

like a knife, edge toward sun;

and next regards its narrow silhouette,

which falls forward from

the hair’s-width feet and runs

beneath the skipper’s form

to lay plain before it on the page,

to demonstrate its shadow-body

as human, without wings: abdomen, waist,

chest and shoulders, a round

head that nods once

beneath twin antennae,

the several legs merging in shadow

to just two. The skipper lingers there,

motionless, for what may seem to a butterfly

a week of time, all in morning.

Suddenly it seizes the air:

assaults the sky flaring above

the waving tips of grass

and swings free,

like the pilot

who ejects, wild-eyed, from the burning

body of his plane to find himself

alive, hurtling in space:

and can tell at once by tenderness

that every vessel in his face,

now bruising grey and golden, has burst.

Jan Bottiglieri is a freelance writer from Schaumburg, IL. Her poems have been published in journals including Margie, Court Green, After Hours, Diagram, and Rattle. She has received two Pushcart Prize nominations, and is an associate editor for the poetry journal RHINO.

Q&A

Q: “The yellow wood, the scarlet poppies on the porcelain ...” Here and in “the summer gold and bronze” of “The Fiery Skipper,” colors are intense and organic. Tell us about color in your life and work–what artist paints your vision?

A: I think that word “organic” really does sum it up for me–I respond emotionally more to color than to form or shape. I love the colors of vegetables, of flowers, of anything in sunlight. That must be why one of my favorite artists is Van Gogh. I’m also fascinated by the words for colors. Someone gave me an artist’s tin of sixty colored pencils when I was a kid, and I loved to read them almost as much as I loved to draw with them. Vermillion… cerulean… aubergine… Don’t those words feel great in your mouth?

Q: I think of Robert Hayden’s wonderful poem “Those Winter Sundays” when I read the line “You practice volition (those boring offices)” in “Homunculus.” Might that have been on your mind? Or perhaps some other reference or source(s) you’d like to discuss for this poem.

A: I love Hayden’s poem, so I’m glad it’s in my head, though I wasn’t referencing it consciously. I wrote “Homunculus” during a time I felt derailed by grief. My daily life (getting out of bed, doing dishes) seemed automatic–as if another person was controlling my actions and that imaginary person was grieving, too. Alchemists believed that feeding a homunculus milk and honey would make them nicer, but I didn’t think that would work for mine. One reference I did have specifically in mind was to the “wizard” of Oz, pulling levers behind a curtain; the dura is a membrane that cloaks the brain, and I imagined peeking behind it.

Q: Did you catch butterflies as a child, and what did you do with them?

A: I didn’t chase butterflies–I much preferred holding very still in hopes that they would land on me. They were fun to watch flying, so why would I want to catch one? I did, however, catch jars full of lightning bugs. I was a kid back in the seventies, when we’d hear a lot about the Energy Crisis, and I remember wondering why we couldn’t just make lamps using jars of fireflies. They were free, and it seems as if there were many more of them back then. At the end of the night I’d let them go because I never knew what to feed them. With “The Fiery Skipper,” I was reading in the grass when the little guy landed two inches from my eyeballs – they’re tiny butterflies, and I’d never had the chance to check one out that closely. I admired its facility for moving between absolute stillness and explosive energy, and I tried to bring the idea of that into the poem.

Poetry from Devon Miller-Duggan

followed by Q&A

Clichés about Angels or How I Decided on a New Philosophy and a New Style All in One Fell Swoop

I don’t really want to make sense of my life anymore.

I just want to find the right dress:

Something vaguely Elizabethan with a huge skirt

in midnight-green velvet. I want that dress

to eat the light. I want that dress

to turn me into an Elizabethan Black Hole in every room I enter.

I want that dress to gravitationally consume

anybody I never much liked anyway.

And not a few noisome strangers while it’s at it.

I want the petticoats, busk, farthingale, corset, laces

and 25 yards of dense, voluptuary silk velvet to

delineate the space designated by me

as me/mine/I. I want that dress to detonate

when I offer my hand to be kissed.

Whoever’s doing the kissing should find him/herself

buzzing like the nap on a wool velvet armchair—red, most likely—

with his/her ears pierced by a couple shards of, say,

windshield, or plastic champagne glass,

or a couple of feathers from a bored angel.

That dress, it’ll skip right by philosophy and become fabric.

Since I’ll have become the dress, eventually I’ll skip

right by being either a philosophy or a bird. I’ll be 25 yards of

thick silk velvet in a green so dense

it passes for black when the light’s wrong.

When I pick up those skirts to curtsey, you’ll see

I’ve gotten flocks of angels to turn into my petticoats

which look like spiral arms of the galaxy.

They’re out of fashion—the angels, not the petticoats–

and need someplace to hang out. The arms of the galaxy

have been ready for aeons to wrap themselves around something warm.

After all those years of listening to us blather on

about the velvet darknesses of space,

those arms long to know how actual velvet feels.

The angels, the galaxy, and me:

Oh, brave vibration.

Found in a Pile of Someone Else’s Postcards: An Anti-Ekphrastic

Not a postcard at all, just a photo of an

enormous Mannerist painting of The Adoration of the Shepherds.

You know it’s Mannerist because all the colors are super-charged

and it’s hard to tell how the bodies got torqued the way they are.

Except the bright baby.

He’s blond—the fuzz of hair is almost a halo—and too relaxed.

The mother holds the sheet back from him like she’s revealing

a birthday cake or a magic rabbit, and the baby’s dead,

no matter how roseate and lit up.

He often is in these paintings, and you know the point’s to play out

all those weighty questions about how the body this child inhabits

is really just a chrysalis.

The cherubim hang out above and watch the scene like it’s television,

and the shepherds beam like the glowy lump is the best word

they’ve ever heard. The Old Masters or their patrons loved this stuff—

the odd babies seated, bare-bottomed, on the cold stone lips of their sarcophagi,

or in their enthralled mother’s laps, reaching up to pinch a nipple.

You wonder whether the brain is just a museum full of Mannerist paintings

and stained documents. What’s the difference, then, between the wings of cherubim

and a thousand sheets of careful calligraphy tossed

from the upstairs window of an archive

by a scholar who’s seen enough?

You decide to settle the matter by repainting the crèche at your church.

Every piece was somehow grey—grey kings, the-same-grey animals, grey Joseph,

grey Mary, grey baby—as if he were a chameleon and was taking on

the greys of everyone else, and the manger and straw as well.

You pull out your paints mix.

The angel’s hair flames copper and its wings become pearl.

The kings wear purples and their mantles’ borders glitter.

The Virgin and Joseph shine softly in their new reds and blues.

The cow’s gone brown, the sheep creamy white,

but the mule has mulishly remained grey, though his eyes now spark.

The shepherds’ robes are all the colors of dirt, rough linen, and black sheep’s wool.

The baby’s just asleep; his cheeks bloom rosy with life,

and the straw around his head’s gone bright.

Devon Miller-Duggan teaches for the Department of English at the University of Delaware. Her first book, Pinning the Bird to the Wall, appeared from Tres Chicas Books in 2008.

Q&A

Q: Why are black holes so very compelling, even absorbing?

A: Black holes are perfect metaphors for our relationship to the extra, extra large and extra, extra seductively terrifying nature of the universe—a physical manifestation of everything we don’t know. And they’re so useful to science fiction writers…

Q: You seem to have some acquaintance with the intricacies of Elizabethan dress. A past life? Have you ever donned a farthingale?

A: Nope, never worn one. I’m a creature very much dedicated to comfort and I can barely stand an underwire in a bra, so corsets and farthingales are not likely to show up in my wardrobe. I do like clothes with lots of fabric, though so I can make an entrance. Maybe in a past life. I’d prefer to think maybe in a future life. Certainly in my fantasy life.

But I’ve always been enthralled by clothes, particularly by historic costume. I wanted, for a while, to be a theatrical costumer. But then I found out how actors treat costumes…

The dress in the poem is a specific dress. It was worn to the Academy Awards sometime in the early ’70s by Sarah Miles (the Emily Prager of my generation). It was a black-green velvet Elizabethan gown. She must have borrowed it from some costume shop. She was drunk off her ass, but the dress was gorgeous. I’ve never found a good picture of it, but I’ve never forgotten it either, though I suspect I’ve altered it a bit in my head over the years, if the one partial photo I’ve dug up is any indicator.

Q: You’re planning a dinner party for the Mannerists. Who would you invite– and how should they be seated?

A: Ye gods. Michelangelo was famous for his dislike of bathwater and abrupt manners. Bronzino and Pontormo would probably need to be separated if they weren’t going to spend the whole evening talking only to each other, but I’m not sure who else I could sit with the famously twitchy Pontormo next to. Parmigianino would probably spend the whole evening trying to figure out how to perform alchemical experiments with any food he didn’t recognize.

I think I’d need to bring in some other folks if the evening wasn’t going to be a disaster. Three art historian friends, maybe, in case the Mannerists were not so good at talking about anything other than art. Several of my wittier and more socially functional friends. Michelangelo next to me because I was obsessed with him in my early teens. All the food brightly colored—that would be absolutely necessary. A white tablecloth and lots of crayons in baskets. Can I have fictional characters, too? Lord Peter Wimsey. I always thought he’d be the best-ever dinner guest no matter who else was at the table.

Poetry from David Salner

followed by Q&A

Nothing, Yet

Nothing is happening, nothing but the night,

lit only by a strand of clouds, gray as a steel sheet. Autumn.

The air has a stillness, almost alpine,

pierced by a dog, barking every so often, echoing. Fresh rain

in the fields, which are stubble and mud,

slanting off in the moonlight, flat to the river’s escarpment.

The voices of men in uniform,

hushed, a uniform purling of voices shapes up, trying to sound

careless but picking the words

with care not to say certain things but wanting a part

in the exchange, on this quiet night,

as if this above all was their duty, to talk softly at night

about what most of all

boys might miss. They smile about love, as if they knew

more than they tell as they rub

their hands by a barrel of fire, share a whisper of longings—

and the deceptions, the confessions, too,

leak into the night, until all the words have dispersed

in the predawn chill, like a mist,

a dew on these ragged fields, as the fictions fade out

and the silence surrounds them

from trench to trench, deep in this basin of night, where nothing

is happening, nothing yet.

What Munzer Said

I thought of Thomas Munzer

as I was making a list—

hamburger, diet cream soda,

bag of mulch, hardy

begonias, and I included

the phone number of an

insurance company, oh,

company, not co.

I added pills to the list,

the kind with a groove so you can

split them down the middle

like seasoned wood. Later that day,

a shower caught me

coming off the mountain. I heard

a clatter of rain on leaves, high up

in the canopy of hornbeam, hickory,

hackberry. The trees filled up

with rain, leaving me

wet to the skin. Munzer said—

all things have been turned

into property, even the birds of the air.

David Salner completed an MFA at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, realized he didn’t want to teach, spent 25 years at trades like iron ore miner and furnace tender. The people he worked with have had a deep impact on his writing. His second book, Working Here, was published by Minnesota State University’s Rooster Hill Press in 2010. His poetry appears in recent issues of The Iowa Review, Poetry Daily, and Threepenny Review. He lives in Frederick, MD, with his wife, Barbara Greenway, a high school English teacher.

Q&A

Q: Might you give us a few lines about Munzer?

A: I may run counter to today’s literary trends, but I find inspiration in the lives of revolutionary figures of the past, people like Thomas Munzer (1489-1525), who led a peasants’ rebellion and was later tortured and beheaded. History is full of insight and courage as well as gore. In his vision of nature and society, Munzer was centuries ahead of his time, and it’s humbling for me, like a walk in the rain, to view myself through his lens.

Q: The quiet presence of duty and of nature pervades “Nothing, Yet.” How does nature prepare us for the life that we must live?

A: The peacefulness of the night before does not prepare us very well for many human experiences, like trench warfare. But that’s life. I’m interested in the way we often remember such dramatic events through details that have little to do with the event itself. We remember seeing a rare and beautiful bird the day we first heard of the death of a friend. We remember watching the heart-wrenching scenes of the 2004 tsunami in a comfortable vacation condo. The way we remember things, hinge them together in moving and ironic ways, hints at our species’ almost limitless capacity for producing art.

Q: Hornbeam, hickory, hackberry–beyond the lovely alliteration, why are those the trees you notice as the rain begins?

A: Great question! They were actually trees I noticed when the rain had turned my hike into a rout at the bottom of the mountain. (Actually, the Catoctin Mountains would hardly be considered even a large hill in many parts of the U.S.) None of these alliterative trees are very tall, either, so they weren’t providing much shelter. Not a great day for me, although of interest in hindsight.

Swimming the Lake by Susan Lago

followed by Q&A

There was the cat in the window and the sound of the clothes tumbling in the dryer. There was the hiss of the gas that lit the flame under the pot of water on the stove, but not the sound of boiling water, not yet. There were the yellow walls and the shadows moving across them in invisible increments and drizzle shushing against the red leaves of the Japanese maple. There was Chardonnay chilling in the fridge and the amber bottle of pills waiting in the drawer for evening when it would be okay to let them out. There were all these things, Jane reminded herself.

Every few days the letters came. The writers of the letters called, too. They had warned Jane, the letters and the recorded voices, but there was nothing she could do about it now.

Dear Ms. Fuck-up, the letters began.

Dear Ms. Winston was what they really said, but Ms. Fuck-up was what they meant. Today’s letter went further, telling Ms. Winston that they, The Bank, regretted to inform her and so on and so forth. Jane put the letter on the table and turned to squint at the clock on the microwave. Ryan would be home from school soon. Each afternoon, when he walked in the door, the clock started moving at its normal speed, but for now the letter had slowed it down and had frozen the lick of shadow on the yellow wall. Even the cat was motionless on her windowsill.

The sun came out and the raindrops on the leaves turned into diamonds. There was that, Jane reminded herself. And the water in the pot, now bubbling on the stove. Jane poured in the pasta. Ryan came home from school and ate his macaroni-and-cheese. He spooned up the orange-colored tubes while pouring into Jane’s ears the story of the day he had just spent in third grade: Ms. Johnson brought them donut holes for a surprise, but Dayton couldn’t eat them because his mom didn’t believe in sugar; a lock-down drill, someone farted but no one admitted it. An A on his math quiz. And so on and so forth. Jane nodded and poured more milk and said okay, one cookie you’ve already had donut holes today, and allowed Ryan to have two anyway.

Jane’s mom, Ryan’s grandma, arrived to watch Ryan so Jane could go to work. Jane’s mom’s name was Alice and she had two deep lines that ran from her nose to the corners of her mouth. Ryan sometimes observed that Grandma looked like Pinocchio when he was still a puppet. Don’t say that, Jane would tell him then; it’s mean. But Ryan heard the smile in her voice and said it again so he could hear it again.

Jane’s mom chided Jane for letting Ryan play too many video games and grimaced when she saw Jane in her red Target uniform. Still no luck, she said, and Jane confirmed that there had been no luck in her job search. Before Ryan’s dad, Jane’s ex-husband, had left, Jane had worked for the pharmaceutical company two exits down the interstate. After the lay-offs, thirty thousand including Jane and Ryan’s dad, Ryan’s dad had decided to move to another state to see if job prospects would be better there. They were and so were the girlfriend prospects because he had both now.

Jane worked Maternity from three to ten. Tania, Jane’s manager, handed her a bottle of Windex and a roll of paper towels. The maternity section at Target was rarely busy so there was a lot of time to fill. Tania’s job was to make sure that Jane filled it. Tania was twenty, but looked about fifteen. She wore her thin blonde hair in a high ponytail. The freckles scattered across her nose and cheeks reminded Jane of Ryan, but the acne, irritated and angry, on Tania’s forehead did not.

Don’t forget to get the base of each rack, said Tania. One squirt per rack and one sheet of towel, she reminded her.

Jane nodded and knelt before a rack of Hawaiian flowers in fevered fuchsia and orange. She wasn’t sure if they were blouses or dresses. Jane knelt and polished and knelt and polished until a very pregnant woman asked her where the bathroom was. In this way, an hour passed. Target time was especially slow. There was music that passed through Jane without leaving an imprint and florescent light that mingled with the smell of coffee from the Starbucks near the register.

Did you finish? asked Tania.

Yes, said Jane even though she hadn’t.

Why don’t you make sure the nursing bras are in size order, Tania said in a way that sounded like asking, but was really telling.

Jane was holding a beige 34C when she heard a male voice from behind her. You’re really beautiful, you know.

She turned. He was Ichabod Crane, but cuter, even if he was wearing the red Target uniform.

What? she said.

I think this belongs to you. He held out a package of nipple cups. I mean to this department, he said and blushed red all the way to the tops of his ears.

Oh, said Jane, taking the package.

I mean it, he said. About your being beautiful. I work over there. He pointed to Electronics, which was down the aisle on the left past Women’s. I’ve seen you. Not that I’m watching you all the time or anything. He blushed again. I’ve noticed you, is all.

Well, thank you, said Jane, not sure if she meant for the nipple cups or the compliment.

I’m Harry, he said and held out his hand.

He had large knuckles and long fingers. Jane shook his hand. Jane, she said.

I know, he said, pointing to her Target nametag: JANE.

She was still blushing as she watched him walk down the aisle back to Electronics.

When were you going to tell me about this? Jane’s mother asked when she got home. She waved the letter from The Bank in front of Jane’s face as if she were fanning away a fly.

Jane shrugged. I don’t know.

What are you going to do? Have you called your shit of an ex-husband?

Sh, said Jane. You’ll wake up Ryan.

Don’t shush me, said Jane’s mother. I hope you don’t think you’re going to move in with me! I really hope you’re not thinking that. Because it’s not going to happen. Jane’s mother plunged her arms into the sleeves of her puffy winter coat. She zipped up the coat to her chin and put a knit cap over her hair, pulling it down so it covered her ears, then picked up her purse. Because I have enough on my plate, she continued. It’s all I can do to keep my head above water myself with the medical bills from my operation.

I understand, Mom, said Jane.

Isn’t it enough I drive all the way across town three, four nights a week to babysit Ryan? Of course he's a love, although he’s terribly spoiled. You let him spend too much time playing those god-awful video games. She looked around the room. Where’s the piano? she asked.

I sold it, said Jane.

They both looked at the wall where the piano had been. Jane had been meaning to buy a plant to help fill in the space, but hadn’t gotten around to it.

How will Ryan practice?

We’re taking a break from piano lessons for now.

What about you? You love to play. There’s nothing more lovely than the way you play the piano. It’s like you go off into another world. Jane’s mother’s face looked damp and heated from the puffy coat and the knit cap and the disappointment.

You better go, Mom. It’s getting late, said Jane.

Jane’s mother sighed. She put the envelope from The Bank on the kitchen table and tapped it with the index finger of the hand not holding her purse. She opened her mouth as if she were going to say something, but closed it against whatever had been on its way out. Instead she hugged Jane, pulling her into the puffy coat that smelled of Jane’s mother’s dog. When she finally released her daughter, Jane could see that her mother’s eyes were wet. Jane wiped a hand across her own eyes and sniffed.

Good night, Mom, she said.

Jane’s mother closed the door behind her quietly so as not to wake Ryan. The cat came out from wherever she had been hiding and rubbed herself against Jane’s leg.

There is this, Jane thought, bending to stroke the cat’s triangle ears.

Mind if I sit down?

Jane looked up from her paper cup of coffee in its protective sleeve. Not at all, she said, and Harry sat down across from her.

I’m on break, he said.

Me too.

They blew on their coffee before taking tiny tentative sips.

Hot, Harry said.

Jane agreed that the coffee was hot.

You look very lovely this evening, he said.

Jane looked down at her red Target uniform. Thank you, she said.

No, I mean it.

That’s better, he said, when she smiled.

They blew and sipped under the florescence.

I used to be in research and development, Harry said after a few moments, and he named the big photography equipment company that had recently declared bankruptcy and laid off tens of thousands of workers. I’m only doing this until something better comes along.

Jane told Harry about her job at the pharmaceutical company. She pictured her desk with its framed picture of Ryan as a gap-toothed toddler, her computer, her telephone, her pile of papers and coffee mug filled with blue and red pens. I miss wearing something different to work each day, she said.

Well, red suits you, he said, gesturing towards Jane’s uniform.

Thank you.

Jane liked the friendly way his Ichabod’s Adam’s apple bobbed up and down when he sipped his coffee.

Want to see a picture of my kids? he asked. He pulled a phone out of the bib of his uniform and handed it to Jane. A boy and a girl. The girl had her father’s lankiness; the boy’s features were fuller, denser.

They’re beautiful, she said, handing it back.

He narrowed his eyes at the phone for another moment then slipped back into his uniform. They live with their mom, he said.

Here’s mine, Jane said, offering her own phone. Ryan was her wallpaper.

Looks just like you, he said.

When Jane got back to Maternity, Tania was waiting, hands on her hips. You’re late she said.

Sorry, Jane said even though she wasn’t late.

In retaliation, Tania set Jane to refold the two-for-one pocket tees on the display table in the front of the department. The table was about the size of a dining room table and stocked with six rows of tee shirts, three stacks deep. Each individual pile had about twelve shirts. The two-for-one pocket tees came in white, black, red, yellow, green, and blue. The table hadn’t been disturbed by a browsing customer since Jane set the shirts out at the beginning of her shift.

All of them, said Tania.

Jane refolded the folded shirts. Once she looked up and caught Harry’s eye across the aisle and when he grinned and tipped an imaginary hat to her, she smiled back and forgot, for a moment, that her feet hurt. When Jane’s shift was over, she found Tania in the stockroom. Tania’s nose was so pink that the freckles didn’t show. Her phone lay in pieces on the floor near a box of maternity support garments.

What? Tania said. Her voice had the same plugged quality as Ryan’s in the crying jag aftermath of a tantrum.

Nothing. Good night, Jane said. Then she said: Are you okay?

When Tania shook her head, strands of ponytail stuck to her wet cheeks. Jane sat down next to her and then Tania was crying into the shoulder of Jane’s uniform. Between sobs, Jane pieced together that something had happened with a boyfriend and a best friend (now former). And now I have no place to live! I’ll have to sleep here in fucking Target! cried Tania, sweeping her arm to indicate the storage room.

What about your parents?

Tania shook her head. I can’t. My dad said if I moved in with a boy at my age that I couldn’t come home again. He said I made my bed so I can just go ahead and lie in it!

I’m sure he’d—

You don’t know him, Tania said. She wrapped her arms around herself and hiccupped.

The front of Jane’s uniform was smudged with Tania’s mascara, but Jane was sure she could get it out. You can come home with me, she said.

Tania was so surprised, she stopped crying. No, she said. That’s okay. I can call a friend.

You’re sure? Jane asked, standing and easing herself towards the doorway.

Noooooo, Tania wailed.

Jane sighed. Then come on, she said.

Outside, the wind was ice. The florescent light was here too and shone on the cement balls that lined the entrance to the store. The balls were Target-red and stood about waist-high and appeared to be bobbing on the surface of a black parking lot lake.

I think that man is crying, said Tania, pointing to a man crouched next to a car with his head in his hands. The car was white and very dirty or maybe it was rust.

Jane and Tania traversed the black lake until they reached the man. It was Harry. Are you okay? Jane asked.

He stood and Jane saw that he hadn’t been crying after all. The car was jacked up and tilted to the side. I lost a lug nut, he said.

Tania and Jane helped Harry look for the lug nut, but they couldn’t find it.

Do you have Triple A? Jane asked. Harry did not.

I can give you a ride home, Jane said.

It’s late and it’s too far. I know you have to get home to your son, Harry said.

You have a son? Tania asked.

Jane pulled out her phone to check the time. Past ten-thirty. Her mother would be furious. The wind blew low and hard and all three tugged their coats tighter around their bodies to shield themselves from it.

You can come home with us, she said.

Tania and Harry looked at Jane. Us? said Tania. Really? said Harry. I couldn’t.

I insist, said Jane. I can’t leave you here.

I’m simply furious, said Jane’s mother before she was even in the door. Do you know what time it is? Do you know how worried I’ve been? Anything could have happened to you. You could be dead in a ditch for all I know. Jane’s mother took in Tania and Harry who were slowly backing away from Jane, but Jane motioned them in with a wave of her hand and shut the door behind them. She unwound her scarf and unzipped her jacket.

Sorry, said Jane.

Jane’s mother picked up her purse from the table, opened it, rummaged inside, and then closed it again. The purse was the size of a shoebox and was black patent leather. Nice, said Jane’s mother. Out with your friends and you didn’t even think to call me.

I’m hungry, said Tania. Do you have anything to eat?

Jane’s mother put her purse down on the table. Hungry? she said.

Jane ducked her head and smiled.

I could eat something, said Harry. He had taken off his coat and hung it on the coat tree next to the door.

Jane’s mother opened cabinets and peered into the refrigerator. Then there were pots on the stove and something frying in a pan. Jane’s mother cooked and talked, moving from counter to refrigerator to stove. She talked about how Ryan spent too much time playing video games and watching TV, described her knee operation last summer, and complained about her dog that refused to let her brush his teeth. She talked about her late husband, Jane’s father, and the lovely funeral they had had for him, was it two years ago now? Jane yawned and let the talk wash over her. Tania had taken her hair out of its ponytail and it floated like cornsilk around her face. When she smiled, Jane could see she still had braces on her bottom teeth. Harry told a funny story about a customer and when they all laughed, the cat leapt on the counter and then to the top of the refrigerator and glared at them with her eyes like cold emeralds.

Is this a party?

They turned. Ryan stood in the doorway to the kitchen, rubbing his eyes against the light. He was wearing his Transformer pajamas and holding his pillow.

No, honey, said Jane. We’re just having a little snack.

Ryan was hungry too so they moved into the dining room so there would be enough room for everyone. We never eat in here, said Ryan. It’s for special.

It’s okay, said Jane. This is special.

Jane’s mother served them plates of eggs scrambled with fresh dill and some boursin cheese Jane vaguely remembered from the depths of the refrigerator. There was turkey bacon and dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets. There was toast and jam and a bowl of strawberries.

One more thing, said Jane, and came back with the bottle of Chardonnay, which was still almost full. She took four of her good crystal wine glasses out of the breakfront. Only a little for me, said Jane’s mother. Me too, said Tania. I’m not even old enough to drink. More for me then, said Harry, smiling at Jane.

They ate until all the food was gone. Ryan nodded in his chair. C’mon, buddy, Jane said. She navigated him upstairs and tucked him into bed. He was asleep before she turned out the light.

Downstairs, her mom was plunging her arms into her coat. Mom, it’s way too late for you to drive home; you’re staying here tonight. You can sleep in my bed.

Don’t be ridiculous. I can see myself home.

Mom.

What about the dog?

He’ll be fine.

Jane’s mom went to bed, still talking as she climbed the stairs to Jane’s bedroom.

Tania, you can sleep in the guestroom, she said, and I can make up the couch for you, she said to Henry.

This is a big house, said Tania. If you live in such a big house, how come you work at Target?

Long story, said Jane.

After Jane had settled Tania into the guestroom with a pair of borrowed pajamas, she returned to the living room to make up the couch for Harry.

There’s still some wine, said Harry, who had cleared off the table and stacked the dishes in the dishwasher, and stood waiting for Jane in front of the fireplace. Let’s make a fire, he said.

Jane had one Duraflame log. She handed it to Harry and he placed it in the fireplace and lit it with the grill lighter that Jane’s ex-husband had bought for this purpose. Then they sat on the couch and finished the wine. They talked about their former spouses and former jobs, their children. Harry yawned, then Jane yawned, and then they both laughed. When he kissed her, he made a quiet sound from deep in his throat. Then he put his arm around her and Jane rested her head on his shoulder until the log had almost burned itself out.

One summer, when Jane had been eight, her brother had dared her to swim out to the dock. Jane had never swum that far before, had never been in water deeper than the height of her own strong girl’s body. She swam fast to keep up with Jimmy who, at ten, far exceeded Jane in size and wisdom. The lake was brown with darts of fairy light. There were things in the water illuminated by the light, but they didn't gross her out because she had grown up on this lake. The water was warm with surprising pockets of cold and Jane swam on after her brother towards the dock. Then she was tired and her arms felt heavy. It was hard to lift one, then the other. Jimmy, she called, but he was too far ahead. She could see his head, brown hair in the brown water. Jane stopped swimming. Jimmy, she called. She sank. The fairy lights showed her a watery brown sky. She broke the surface, striking it with her arms, willing it to hold her up. She sank again and rose again. Water filled her mouth and nose. Then her foot glanced against the grit and slime of the bottom of the lake. She put the foot down, then the other. And realized that if she stood on tiptoe her mouth and nose were free. She didn’t even mind later when Jimmy called her a baby. She didn’t tell him how she had almost drowned but saved herself when she realized that if she put her feet down she could stand and simply walk herself out.

That was long ago, but Jane remembered the feeling of relief. Mostly, she remembered how embarrassed she had been to discover she wasn’t drowning after all.

Hey, buddy, move over, Jane said, nudging Ryan to the inside edge of his bed.

We’re having a sleepover?

Yes. Now go to sleep.

Mom?

Mmmmmm? Jane was almost asleep.

Can they live here with us?

Jane opened her eyes. Who?

Tania and Harry. They’re nice. And then we wouldn’t have to give our house to the bank.

Don’t be silly, Jane said. His face was inches from hers, their noses almost touching. How did you know about the bank? she whispered.

I hear stuff, said Ryan. So can they?

I don’t think so. I don’t know. We’ll see, said Jane, but Ryan had fallen back to sleep.

Now there was only the wind and shards of ice that hit the window with sandpapery rasps. There were the metal baseboards pinging with the rising heat and the lingering smell of bacon. There were the beds with the people sleeping in them and dreaming in them. There were all these things, Jane reminded herself.

Susan Lago is a lecturer in the English department at William Paterson University. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in publications such as Per Contra, Monkeybicycle, Verbsap, Word Riot, as well as Pank Magazine who nominated one of her short stories for a 2011 Pushcart Prize. In addition to having a Master of Arts degree in English from William Paterson University, Susan serves as a nonfiction editor of the university’s literary magazine, Map Literary.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this story?

A: I was inspired to write “Swimming the Lake” after the school year ended and the beginning of summer was only seconds away. Driving past my town’s beach club one day, I remembered the time when I almost drowned, the feeling of utter panic, and then my embarrassment when I found that I wasn’t drowning after all. I’ve tried to keep that in mind—the feeling of being able to save myself—when dealing with the various problems life throws my way.

Q: What writers do you consider to be your primary influences?

A: Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro, John Cheever, John Updike, Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Franzen

Q: What’s your ideal place to write?

A: In my house with my cat drowsing nearby.

Q: Who plays you in the movie in the movie of your life?

A: Sarah Jessica Parker. It’s the shoes.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: I’m working on putting together a collection of my short stories as well as seeking representation for my novel.

Continental Divide by L. McKenna Donovan

followed by Q&A

It would have been difficult to admit what I was feeling. Easier by far to focus on the hard, Wyoming clay under my heels, or on the bitter wind that beat against me and whipped my long, heavy coat against my calves, but the mourners deserved my attention.

“Beautiful service. So sorry for your loss.” Thank you.

“So sorry. We’ll be praying for you.” Thank you.

“My dear, I’m glad you brought him back home to rest among us.” Thank you.

“So sad. I know you’ll miss him—”

—Miss him. My eyes turned to the burnished casket resting over the draped grave. Once the mourners were gone, the cemetery staff would come forward and lower the casket. After all, as the young priest had so solemnly promised from the graveside, “He was a cherished friend, son, and husband, and our memories of him shall remain untarnished and vivid.”

Vivid. Yes, indeed, our memories of him—

A hand touched my shoulder. “My dear, will you be all right?”

I startled, then turned, thankful that a lash of wind brought tears to my eyes before I glanced up at the face above the black cassock. “Yes. Yes, I’ll be fine, Father. Thank you.”

Despite my preoccupation, I realized how dismissive I sounded, and the good priest deserved better from me. I hastened to fill the silence. “Wonderful eulogy, Father, thank you. I know his mother will take comfort from your kind words.”

“You’re welcome, my dear.” His hands offered warmth to mine, but his eyes? Yes, his eyes registered my slip—the inadvertent confession that the comfort of his eulogy belonged not to me, but to my late husband’s mother.

“Julia-honey!” My grieving mother-in-law picked her way through clumps of brittle grass, stopping long enough to claim the priest’s hands. “Oh, thank you, Father. Thank you so much! Yes, indeed, his last months were so terribly difficult…so hard on me, living so far away from him. At least he’s home again. He was always such a fighter, but this? Oh, he would have loved your sermon, just loved it. He had such a way with words. A lovely way with words . . .”

Yes, indeed, ‘a lovely way with words.’

—No, no. The black dress. It manages to make you look elegant.

—No, no, no! That’s not the way to do it. Here, I’ll write your damned résumé.

—Just bring your proposal with you. No one at the barbecue will mind if you sit inside and work.

“Julia-honey?” His mother fussed her hair back under the stiff, black netting. “We’re going back to the house. Everyone will be there, and Father Murphy is joining us. You really should—”

“Mum, his friends have come to see you, and I have to drive back home. I have only three more days of leave, remember? And it’s a long way to—”

“—to Seattle, yes, yes, I know. Really, you should have flown so you don’t have to drive yourself and I hate to think of you being on the road, particularly now that you’re alone and things happen, you know—”

“Mum—”

“—and he certainly wouldn’t have let you drive by yourself, especially at night and especially that far! Oh, dear, and it’s so hard to accept that he is gone. My beloved son. Well, no help for that. At least he’s home again. God giveth and God taketh away, you know. You’ll come back for Christmas, of course. You’re still family, no matter what anyone else says, and you’ll feel better if—”

—if you wear the black dress . . .

—if you let me do it . . .

—if you come back for Christmas . . .

* * *

The drive home was suitably long. I refused to turn on the radio, the new silence too precious to fill with empty words—words of bright-speak disc jockeys, songs of love-sweetly-lost, promises of lifetime guarantees. Besides, the jagged mountains had always felt closer, more ancient and wise and intimate without the sound of human voices. Maybe if I listened closely, the aspens would whisper their broad-rooted secrets to me—

I immediately repressed the thought, but wait . . . there was no need. Old habits die hard, and it no longer mattered that he had never understood the mystic in me. I laughed, suddenly and joyfully, and it startled me. That was the first sound I had made in over three hundred miles. I rolled down my window and sucked the frigid air deep into my lungs.

With the window still open, I headed over the pass, but at the top, a roadside marker caught my attention. Another impulse. I pulled over and stared at the sign. White letters on slate-blue background: Continental Divide. Around me the Douglas firs stood straight and tall and free to the sky, and the aspens shivered gold in the mountain wind, their leaves skittering across the first flurries of snow.

Continental Divide. Behind me, all waters flow east, back to Wyoming, but in front of me, they flow west, onward to the Pacific Ocean. In my rearview mirror, I let the darkening sky hold my gaze for a long moment, but through my windshield, the sun was warm in the western sky. I set my mind toward the Pacific, the radio still silent, and my window still open.

Late the next day, the Cascade Mountains appeared in the distance, their winter shoulders sadly bare, for the year had been dry. Then several hours afterwards, I came over the pass, and spread below me was the skyline of Seattle and the familiar waters of the sound glinting under the late-evening moon. There was time to catch the late ferry, though I dreaded the crossing. As much as I loved to sit on rocky beaches and stare at the million pricks of sunlight on choppy water, seasickness was my bane. This, however, had not prevented him from buying a 30’ cruiser. How long must I wait before selling it now that he was gone?

The ferry was filled with passengers, some subdued from a long day in the city, but others chattering, laughing, celebrating an evening’s entertainment. Always the lovers arm in arm, and always the parents with children asleep against their shoulders. I did not get out of the car, enduring in solitude the pitch and shudder of the ferry caught by the strong crosscurrents of the changing tide. It did not help to count the minutes to the dock, so it was with great relief that I was finally able to nudge my car up the ramp and onto dry land at the beckoning of the ferry worker.

An hour passed and the roads narrowed: four lanes became two, homes receded from the verge, trees laced overhead, and leaves slept in rain-washed ditches. The house was deeply still, and as I kicked off my heels in the entry, I savored the silence. And the lack of his impatient voice.

—Did they sign the contract? Yes, but—

—Did you get your bonus check yet? Yes, maybe we could now—

—We should have children soon. You’re not getting any younger, you know. Yes, I know.

* * *

It is my first morning alone. The house is open, windows and doors unlocked and unlatched and thrown wide to the freezing morning air. The rough cedar deck overlooks the canal, and I watch the sun rise on gentle toes, traveling from the tips of the firs, down through the spread of branches before reaching their night-damp bark. My coffee is warm and darkly fresh, and I cup its warmth between my palms and lean my elbows on the railing. The tide is low, and the gulls forage for shrimp and mussels left in tidal pools by the retreating water.

The air smells green and damp, a bit acrid and yet so very alive. My collie-girl hustles to the shore, head lowered, her gaze intent on the flock before her. I sip my coffee and watch. She poses for a vivid black-and-white moment, then charges. The seagulls scatter and screech in a maelstrom of loose feathers and dropped shells.

I laugh, and my delighted sound carries over the water.

L. McKenna Donovan: Writing addict. Star gazer. Obsessive reader. MFA. Collie aficionado. Plant whisperer.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this story?

A: At any given time, we actually carry on several conversations besides the immediate auditory one. These other conversations are found in our unvoiced (or even subconscious) thoughts as well as snatches of relevant conversations from our past. This story makes one such ‘tiered conversation’ fully visible.

Q: What writers do you consider to be your primary influences?

A: Pearl S. Buck for her ability to bring foreign cultures into brilliant dimensions; Mary Stewart for her ability to bring settings alive to our senses, especially Greece and England; Aaron Sorkin for dialogue that never disappoints.

Q: What’s your ideal place to write?

A: Italy. Failing that, my office (in my home).

Q: Who plays you in the movie in the movie of your life?

A: Susan Sarandon

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Within the next two months, I’ll complete my current novel of transnational intrigue set in 1961. Concurrently, I am working on a collection of supporting short stories, which reveal life-informing events from those characters’ early lives—events which are alluded to, but outside the scope of the novel.

My website, To Write Well, is currently under construction with a self-imposed deadline of August 1, 2012 for offering two online writing courses that focus on ‘just the right word’

Things I Would Say to Certain People by Ryan Meany

followed by Q&A

One of My Students

I could have fallen in love with you the first day of class, circumstances notwithstanding. Then you spoke, and again and again, determined to show how little you knew. You were so proud of that little bit, so graceless in speaking it. Stop. For them. For you. Why not be gorgeous? Listen most of the time, for a long time. A great number of women, too many, are working very hard right now, right as you are not reading this, to be as beautiful as you are when you are silent. And that smile.

Mentor

Say it, coward: I’m too simple, young, awkward, ignorant for us to be best friends. You’re heartless. I’m here if you change your mind.

Old Friend Who Called Off the Friendship

Fifteen years we were sort of together, off and on, and you tossed all of that as you might a receipt at the bottom of one of your scuffed knock-off designer purses. A year and a month and a half later I wish you would call so I could hurt you. All those blowjobs you gave me in college, and the years of sex, late-night drunken “Do you have any idea how long my day is tomorrow?” sex. What does all that sex become if it will never happen again? And all of that which was better than the sex, as I was getting better sex elsewhere: the years of conversations about our football team and murderers you were convicting and books I thought were better and my life. You do understand that all of it is now a crumple under a heap in a place people rarely visit, find no happiness in. You do know what that says about you.

I was never going to marry you. You, more than anyone, knew you were shaped like an egg. You knew how skinny and hairless I was in high school, how the girls flirted but never dared. You, of all people, knew how much of my life I would spend proving.

Mentee

I’ve said everything I’ve been paid to say. Please ask someone else.

The Middle-Aged Woman I Pass in the Hallway at Work

Who Wears a Dolly Parton Amount of Make-Up

But Has Not the Means to Acquire Make-Up of the Same Quality as Dolly’s

or the Skill to Apply It as Dolly, or Her People, Do

I would totally have sex with you.

The Homeless Woman I Met Around 4 A.M. on New Year’s

I hope your daughter has found you. I hope the ending of your book was satisfying and the blankets were sufficient. I hope you found somewhere to stay when the temperature dropped even lower. I did think about you on those colder nights, when I was in my bed. I have not been looking for you though. In fact I have probably tried not to see you again. I hope you didn’t just look twenty years older than I. Do know that when I am old enough to be sure you are dead, I will regret not trying to see you again. Surely I will now.

James Joyce

I’ve argued the genius of Ulysses for years. I might have even inspired one or two people to read the first few pages. But what the hell are you talking about?

Ophelia

I know you’re a dog, don’t really fit here. But I love you, really love you, so much more than anyone I’ll be talking to. Come lick my face you sloppy dumb little love.

Uncle

You’re over there praying and praying (Do you actually get on your knees?) and believing so hard and you’re doing it all, really, to avoid eternal stink and hot, and you know I’m not doing the same, so you must believe I’m going to hell.

Can you love someone you believe is going to hell?

Vera

I almost found you once, I like to believe. I searched for your address online, drove all the way to Starke, Florida where your dad took you when he took you away. (God, how did you ever live there? I mean, dude, you would think the town that executes all of Florida’s needing-to-be-executed would not actually look like a town that kills.) A nice man in the neighborhood, a few doors down, said, “Yeah, a couple women lived there. Moved about two months ago. I didn’t really know them.” After twelve years I was two months late. I wish I would have asked him, “What did she look like?”

“Which one?”

“The—I can’t really describe her. She had short hair in eighth grade. She was then possibly showing signs that with age she might become overweight.”

“Oh, the fat one?”

“Yes. Did she have green eyes? Were her lips almost always pursed? Did she look like she would be exactly as shy and excited around me as I would be her? Exactly?”

“I don’t know. She was pretty fat.”

I will take you anyway, Vera. You could be severely burned. And I like chunkier women anyway. And diets. There are diets for us, Vera. (Now that I think about it, I don’t know if I could deal with the burns. Like if your whole left ear is gone or something? That would irritate my nice memories.)

Eighth grade. And after you and I went to Disney World with my parents to make our last memory I cried and cried in my bed that night until my mom came in and said, not in these words, “I know it’s hard now, but you’re so young and so many more are out there, young like you. You will meet them someday and they will love you and you will, eventually, hurt them worse than you are hurting right now.” I don’t think even I believed back then I would love you forever when I told you I would love you forever in fancily folded notes. But I guess the child me was warning me. I never liked that kid.

Jessica

Actually, I’ve said it all already, which is part of our problem. And is why I can’t seem to start over with someone else. I mean, that was a lot of stuff I said. Who wants to do that a different way all over again?

Road-Raging Trucker Who Pulled a Handful of Hair Out of My Head

You lucky, sad son of a bitch. Only because I’m a petite man did I not follow you all the way to your next stop and beat the bad memories out of you. Oh, but had I my father’s arms and rage I would kick you back into your mother’s twat so you could start over. And if you fuck up your life this time too we can just keep on doing this until you get it right.

You were right about one thing, though. I should not have swerved in front of your semi, slammed on my breaks and jumped out of my car.

Dale Earnhardt, Jr.

Please read this and think I’m cool enough to hang out with. I’ll trade you the “8” on my keyboard for one of your hats.

Mr. Derek Brooks

Do you read? If not, I understand. If I played in the NFL, was a future Hall of Famer—actually, if I played in the NFL and sat on the bench I wouldn’t read.

The Attendees of Mandy’s Funeral and Mandy

We must have felt similarly. Any funeral held for a suicide victim is pretty damn sad, but this one especially. Of the forty people attending, only about ten of us were truly there for her and not just for Jeff or just because we were somehow associated, and except for maybe three or four of us, we all knew we had not done much to keep her around. If each of us had spent another five minutes a week talking to her or, in most cases, had spent at least five minutes period, we might have bought ourselves time. If we could go back in time—be honest—how long would most of you continue to call her and when she didn’t answer get in your car and find her?

I sense most of you, like me, never liked her much. She was usually aloof on the rare occasions when she did socialize. Yes, I know we wanted to like her. Anyone who saw those eyes wanted to like her, a blue like blue Gatorade in a backlit glass, and the size, seemingly, because of their brilliance, of golf balls. And we wanted to like her because she had, from time to time, when she was in the mood, showed us how easy liking her was—her gooselike cackle, her capacity to shift conversation from recent psychological theory to the Simpsons to a dick joke. So good for you, Mandy. One hell of a point you made. I was mad at you for doing this to Jeff until about three sentences ago. But you were right. Fuck us all.

I sometimes think of you being in the ground, what you must look like now. The night you did Yoga on the floor in front of me and I asked you to stop, insinuating you were teasing me, turning me on, which you knew, which was, I would find out in about twenty minutes, why you were doing it: I could have never foreseen that always tugging at such a pleasant memory would be the story of Denise and Kayla arriving before the police did. They had come to see, to believe, your darkening, stiff body, the small but dense change you would force into me.

The Feminist Who Encourages Me

I found oppressive your use of the word misogyny to describe “One of My Students.” I can never convince you that I am quite capable of embracing both my hormones and women. Because I love you too, I have revised the passage:

I would have fallen in love with you the first day of class, circumstances notwithstanding. I knew some day all that potential would bloom out of those full lips and you would be loved by so many men. May they be useful, if you want them. May they not carry you but support you, not patronizingly but lovingly, if you want them to. May they see and wish to smell only you. May they walk, drive, roll over whenever you want them, and may you want them, if you want to want them, in a long life.

Ideal Woman

. . .

Jesus

Please come back and tell them you were speaking metaphorically.

The People in Restaurants Who Cheer When Someone Drops Plates

You are the same people who do not look away when a man sneezes snot into his hand. You do look away from the girl in the wheelchair. And you have no trouble choosing which puppy. Oh, you hold the door open for the old man. Sure. Everyone is watching. But when you see him walking home with bags of groceries, when you are safely in your car, you drive on. You are the reason we war. You will not see the connection. So we are at war. You are the reason children are homeless. You enjoy zoos. If you have any sincerity in you at all, you are the ones most likely to hurt the ones who love you. And the ones who do not love you, have no reason to, the clerk at the gas station, you would shit on him for twenty dollars if he promised not to watch.

In that moment right after the bang and shattering, the person’s food on the floor, the waitress humiliated, even more busy than before and now possibly making even less money, you’re glad. You’re glad this time you can join in. The last time it happened, some other restaurant, some other humiliated person, you were too cowardly to join in. You’re satisfied to hide your jeering among jeerers. You are behind the lynch mob, not really part of it but absolutely it.

The Girl in the Wheelchair I Continue to Look Away From

I want to be better than this. Not because of hell but because I want everyone to love me. Understand why I do not smile at you: I do not want you thinking I’m smiling because you are down there, bent, not someone I would have sex with. (Can you have sex?) So what am I supposed to do? Say hi? But what if you want to be my friend? Come with me to the bar? I would love to have you, but I do not want people thinking I’m bringing the broken girl to the bar just to be charming, although that would be a reason. Yes, I know I’ve brought many broken girls to many bars. But because your options are limited and because I would be so carefully nice to you, you might possibly begin to love me. I do not want that. I know I just said I want everyone to love me. But from a great comfortable distance. Besides, I cannot do for them all that you must do to keep people loving you. No, I am sorry. I will start smiling at you, but that is it. It’s an entirely different matter to hurt a broken girl who can walk. You must be so beautiful.

Hitler

I saw you in a movie some time ago and you were nice to your secretary, and she really liked you. It was easy to believe. You are a bit of the antichrist in the sense that Jesus was immortalized after dying for sins and you became immortalized, mainly, to embody sins. I guess the idea is if we can keep hating you for being so hateful, we don’t have to confront ourselves. Plus, it’s just too tempting to make evil about numbers (“He killed so many more people than I did”). That this line of thinking would likely piss Jesus off is not really what I want to say to you. What I wanted to say is only because you are dead do I not feel bad for you. I wish I could have been your secretary for a day when you were in a good mood—even though I realize your good mood might have been the result of your having killed a lot of people the day before, but that was going to happen eventually anyway. And I wish my video camera had been invented and I happened to bring it to work that day. After you were finished killing Germany and yourself, the Germany we beat into a monster and handed to you, I would have traveled with the circus, set up camp right next to the freak show, and shown people how nice you were to me, bringing me a flower, patting my hand, Eva in the background rolling her eyes.

Inventor of the Plunger

I refuse to research you. If you were a lunatic or a bore I’d rather not know. I’m thrilled to know you were thinking deeply about shit. I hope you were a woman, some nanny-deprived womb-ravaged mother who had an intuitive understanding of physics and refused to give the plumber one more penny. Your invention is so simple and perfect it has not been improved by time or better minds. I must apologize. While the plunger should be kept somewhere in our living rooms—if not for its brilliance then at least as a reminder that most of the horrifying moments in our futures have already been considered and dealt with countless times—we still hide it, if not in the corner behind the toilet, which is hidden in its own corner, then even farther away. But if you understood the repercussions of your genius, you understood the thanklessness of it. If you were compelled to invent the plunger, you understood our disgust for ourselves.

I would still rather not travel to the library, or call a librarian, but according to the consensus on Google right now, your name is Jeffery Gunderson. Barcaluv of Answerbag.com adds that you were a farmer in New Jersey who created this chef d’oeuvre after becoming frustrated by constipated cows. Oh I hope this is true. Please say poop-clogged cows were your inspiration.

Even Wikipedia refuses to verify you. So does Oxford Reference Online. No surprise there, really. Encyclopedia Britannica Online politely offers others when your name is searched: Robert Joffery, for example, who was a fine ballet dancer, and Lord Francis Jeffrey, who wore a wig and judged Scottish literature and criminals.

Great Great Great Grandmother

Some have said you were a hateful bitch. My cousin Kelli, who was born kind and taught herself to think, says you were the daughter of a white man and a Cherokee. Of course he left before you were born and, probably because of this, your mother despised you. By the time you were fourteen you would abandon your own daughter, whom I would know only as Granny, the ancient woman who broke her hip in our garage when I was twelve, then spent the last several years of her life, except holidays and birthdays, in a macabre nursing home, which, aside from the memories it resurrected, was still not as terrifying and loveless as the sanatorium in which she spent her first several years.

You understand why I didn’t see the point of attending your daughter’s funeral. It was a little late to care. Even though you were the first to abandon her, and the last with an excuse, left her in that ungodly home for orphans, invalids and crazies, her daughter came to you anyway, the one I would know as Memaw, an old woman who smoked and gave me Ritz Crackers, her skin like a discarded chamois. I could not eat Ritz Crackers for years because of that skin. But long before she was a gross old woman, my cousin told me recently, she was combing your hair and saw the scars on your scalp, the dents in your skull. You let her run her fingers over them but only said, “Ma was tough.”

Surely you have a lot of regrets. We are a very regretful clan. So you might be happy to know that the women who came from you have been very good to me and I have yet to abandon them.

Young Writers

Get an MBA and keep a diary.

Luc Donckerwolke

If my pronunciation of your name is close, it sounds like someone falling onto a deck. This is appropriate since, if I were, for some stupid reason, given your masterpiece, the Lamborghini Murcielago RGT, which I also cannot pronounce, I would faint.

I imagine you meeting Michelangelo, saying in German (you are German, right?), “I’ve always wanted to see the Sistine Chapel. In person. It looks so awesome. How long were you up there, on your back? That’s crazy. How did you do that? You madman! Here. I have to show you this. If you’d indulge me. It’s not the Sistine Chapel, but—I’m proud of it.” And Michelangelo, in his frill and robe, stunned still by you, Mr. Donckerwolke. Awed by your— He doesn’t know what to call it. A castle? All these clean, smooth edges and objects, the alluring wickedness. All this space and light. And how is the weather so perfect?

You lead the little old man to the Murcielago, and he, one of God’s favorites, stiffens. He doesn’t know whether he is afraid, awakened or damned. You wish he would say something. Are his eyes watering? You catch him before he hits the floor. He is frail in his robe, light. You ease him onto the floor and gently slap his loose cheek. You don’t know what else to do. Did you, after such a disciplined life, just kill fucking Michelangelo? No. No, don’t worry. Soon his eyes open. He is not dead. He is petrified, and he is still in this place, and that thing still there, demonic beauty with something like eyes, a black darker than any memory of night but a black that glows. A serpent, all head. He is sure it will speak. Satan himself will exit its jaws. “God, I have not failed you!” screams Michelangelo in what, in fact, sounds to you, Mr. Donckerwolke, like the devil’s language. Until you realize it’s only perfect Latin. “I will see this no more!” Michelangelo continues. “Get me out of here now!” The old man, with all his mortal effort, stands and runs into the door. “Open this now!” You try to sooth him. “It’s only a car. Like a carriage?” He paws at the door, a scared dog. You escort him away from your masterpiece, do not dare say the only thing you can think of: “But you haven’t even seen what it can do.”

People Who Drive, Myself Excluded

If you are a fair representation of humanity, I see no hope for peace. Most of you I hate. You ride my ass or insist I ride yours. You pull out in front of me and do not accelerate appropriately or, when I pull out in front of you, you are speeding inappropriately. And you. You who uses the rearview mirror only for rosary beads. You who refuses to move from the left lane when I’ve made quite obvious I’m faster traffic. I understand why you wonder whether God likes you. Or you, the middle manager, your suit stiffer than your cock’s been in a decade, you and your crusty briefs weaving in and out of lanes like a spring breaker. The world will not miss you. And lady, seriously? Because your turn is right up here and, after all these years, you still cannot drive empathetically and think about your coupons at the same time, are you really going to cut across three lanes? Yes, of course you are. Instead of driving on to the next intersection and turning around, instead of asking yourself, “Will my destination still be there if I am delayed three minutes?”, you stop traffic. In three lanes. You risk everyone else’s spilled coffee and insurance rates because three minutes and a quarter mile are just too much to bear. I too wonder why your kids don’t call more often.

People Who Drive, Myself Included

We are not vehicles. We are people negotiating space, and we are doing so at several feet per second, and we are doing so in a hollowed-out boulder. We have not, remember, become this boulder. We are in it, and we are propelling it, at several feet per second, at other people. That we cannot see these people as we might if they were standing in line or walking down a hallway does not mean they do not exist, that they cannot die. That they cannot see us does not mean we are not, like them, still obliged to negotiate. They and we are we and we have mothers and lovers. We have cousins who want to hear from us and old high school friends who’d rather not have their next reunion ruined by our feathery obituaries.

Girl in the Wheelchair After I Smiled

You looked away? Not even an acknowledgement? Both times? After all that? We should make out.

Those Who Have Divorced Because of Money,

Sex, Interference of a Third-Party,

or Television

No shame in being the majority. We must all learn the hard way that love is a liquid, not a solid, and some of us will.

Freaks Between the Ages of Six and Thirteen

All of you, the gimps, the pant pissers, the too-tall and the late blooming, the birthmarked, the beaten, the narcoleptic, the hypersensitive, the abandoned and the all-of- the-above. The worst of you are, in fact, the luckiest. You are dumb and cannot become much smarter. You will never know how much they could hurt you. Stay with your loving mom. Or your dad. Live in his attic. Live in her basement. You’ll have many happy years before he or she dies, and then your greatest pain will probably be your last. If neither your mother nor father loves you, find the people who need to love you. They are everywhere. If even this thought scares you, color. Paint. Someone will insist on protecting you. No one knows what we are capable of.

The rest of you: get good at something, anything. Now. To hell with your childhood. It is ruined. This will not matter someday when all these beautiful people are confused and nostalgic. Ski, read, find a horn and blow. If you’d rather get laid sooner, sing or learn the guitar. Best case scenario, do both. Play the harmonica for all I care. Just play and one day love will smother you. Of course you will be hurt a lot along the way, but this is good. You will sound much better.

Myself

Unlike real people, fictional people exist only as long as they are wanted. And so you are finished. You have become irritating.

Your mother and father, whom you’ve cut from this in a grandiose act of cowardice, could have been mature and enlightened before they conceived you, one an architect, the other a pathologist, inculcating in you a firmer sense of logic, a broader imagination and a healthier notion of mortality. You could have been lovely and quiet. You wouldn’t do that to yourself, though, because then you wouldn’t need you, and then they wouldn’t have existed, nor would have Jesus, Dale Earnhardt, Jr., coupon lady, etc.

So go speak one last time to whomever. Try not to make an ass of yourself.

Audience

I hope you would call if I gave you my phone number. I can’t, though. A better writer has already done something like that, and it didn’t work out very well for him. Not to mention you would be very disappointed. If I were able to put my best self forward in real life I wouldn’t do this crap.

Even though I know how detestably you can need their affection, I suppose you cannot love anonymous people. So I won’t say I love you, even though I kind of want to. Plus, loving abstractions is childish and cruel. I had a girlfriend do that to me once. What she wished I was she stapled to my forehead like a photo of Johnny Depp. I didn’t even realize she’d done it, I was so in love, until the worst possible time: when she was dumping me. The wind—nothing more, really—had lifted the photo from my face one too many times. Ever been through that? Most deflating breakup ever. There you are dumped and for the first time realizing you hadn’t even been loved. All you can do is pull the staple out, look at the photo and weep. At least when you get dumped by someone who really loves you, or really had loved you, you can hate yourself and grow. But now, on top of that sense of your own impending desperation, you see for the first time two people can actually only think they are in love, and one of them can be you. She said things like, “Someday you will understand,” and I didn’t know whether to die or kill. No longer do I question the romances that end on the news.

Anyway, this is all to say I want to love you. I hope we meet again like this, disembodied and hopeful. You mean too much to me.

Ryan Meany’s work has appeared in Story Quarterly, Crazyhorse, Confrontation, The Pinch and other places. It’s forthcoming in Otis Nebula.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this piece?

A: I think I was fantasizing about telling people I know what I really really thought.

Q: What writers do you consider to be your primary influences?

A: Among others: Barry Hannah, Padgett Powell, Emily Dickinson, Alice Munro, Raymond Carver (of course), James Dickey, and Robert Bly.

Q: What’s your ideal place to write?

A: On the couch, feet on coffee table.

Q: Who plays you in the movie in the movie of your life?

A: Someone with little more than a Wendy’s commercial and community theater on his resume.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: A poem about a maiden on a horse with a knight who has just saved her from a dragon. So far she’s bracing herself for the terrible things about to happen to her.

Its Eyes Was Flickering by Joe Samuel Starnes

followed by Q&A

June 17, 2009

Memo to the Honorable Franklin T. Stone III, Interim Director

Georgia Bureau of Investigation

From: Agent Ward “Sonny” Hawkins Jr.

RE: Inactive Status Case Request GBI-2001-4356