Prime Decimals 31.2

State Capitals

by Aaron Burch

followed by Q&A

“Ask me any of them,” the kid says to the man, not clarifying, not caring that they haven’t been introduced, just pushing a book, open to a map of the United States, toward the man.

The man looks to the woman. He isn’t sure what the kid means, what he’s supposed to ask. Isn’t sure the protocol here.

The man is over for dinner. They had a reservation, but something happened—the kid got sick, or the babysitter got sick, or someone in the babysitter’s family? Someone was sick, or maybe the man made that up or misremembered or misheard, but she apologized profusely. This was the back-up plan, this seemed to be a thing that happened—the man was sure he’d seen the scenario in countless movies, but still it caught him by surprise. He’d never pictured himself in those movies. He couldn’t imagine having a kid himself, he’d never before been out with a woman who had a kid. A woman who was also a mother. The man didn’t really think of himself as a man, not in the adult way, not in the men know how to fix things, and build things, and are adults and adults have kids way, despite many of his friends being married and starting to have kids, owning homes, having second children. But here he is, sitting for the dinner she made him, and now here is her son, who she said would likely stay in his room all night, playing video games and being quiet, but who now wants to talk about… his homework. Or is geography only a hobby, something to show off?

“He’s learning the state capitals,” the woman says. “This is Matthew. Matthew, can you say hi?”

The kid—Matthew—doesn’t say hi, just continues to stand waiting for the man to “ask him any of them.” The woman smiles at the man, smiles at her son.

The man looks down at the book, holds it in his hands. It has that feel of a grade school textbook that he hasn’t felt since being Matthew’s age himself. He remembers the feel of his small, 3rd grade chair and desk, all one piece and wrapped around him like a cockpit. He can see Mrs. Butcher standing at the front of the room, writing on the chalkboard; can hear his parents teaching him to use mnemonics to memorize all the state capitals. The man thinks about it, can only remember the capitals of the three west coast states he lived in growing up. He’s lived in numerous states in the decade since but can’t recall for certain any of their capitals, much less the states he’s never been to. South Carolina? Maine? He can name the biggest cities, the college towns, but can’t remember seeing a capital building since grade school field trips. Can that be right? Is all that knowledge only necessary for kids in school and people that go into government? What else has he learned and forgotten?

“Califor—” the man says, but Matthew answers before he can even finish,

“Sacramento!”

Too easy, the man thinks, but says, “Good job.” He again looks down at the map, makes like he is tilting it away from the kid so he can’t cheat. He tries to find a tricky one, the one that looks least familiar.

The man imagines sitting with Matthew, the kid teaching him, reminding him how to remember. Learning together the years each state became a state. All the Presidents, in order. Moving on to countries and their capitals. Official languages, largest national exports, wars they’d been in. An entire growing up of learning, and this time the man can pay better attention. He can encourage Matthew to take guitar lessons, and learn alongside him. If he wants to play baseball, or soccer, or basketball, the man can volunteer as a coach, but he should probably dissuade football, it’s too violent. He can start talking about colleges when the kid gets to high school, not to pressure him, but to let him know the world of opportunities that exist. He’ll buy him his first car, and he’ll encourage taking an automotive class so they can work on the car together, too. Do high schools still offer automotive classes? Woodshop? He can buy power tools, a table saw, turn the garage into a workshop and they can learn to build things together. Maybe build an extension on the house, or at least a deck, or some kind of studio in the backyard. Maybe the kid will be an artist, and the man will encourage him to learn how to paint, to write, to become a filmmaker. He’ll prepare him for the world, promote all kinds of learning and discovery. He’ll teach the kid any and everything, learning alongside him, teaching the kid all those things he believes he learned too late in life himself, and learning together everything the man believes he missed out on.

The man starts to feel a tightness in his chest, a welling in his eyes. The kid is already leaving, moving out, going to college, calling often and coming home to visit, but then doing so less, graduating, moving out of state, far away for graduate school or a job or a woman and visiting less, it’s so hard to find the time, and the money, and he’s starting a family of his own, and the man is proud of the man Matthew has become but misses the kid, and how he would take care of him when sick, and how they used to be able to spend so much time together learning something as simple as state capitals. How did time pass so quickly? The man isn’t ready to say goodbye.

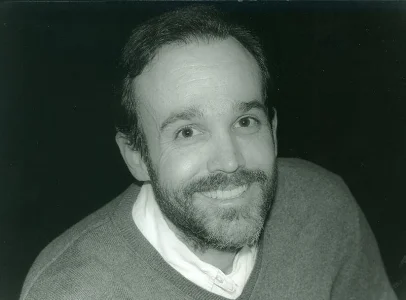

Aaron Burch is the editor of HOBART: another literary journal and the author of How to Predict the Weather.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this story?

A: I don’t actually remember the specific inspiration/genesis for this short, other than something (a TV show? Scene in a movie? Something I was reading, either a book or even a submission for Hobart?) reminded me of all that info you learn as a kid, both in books as an interest (the wealth of dinosaur names, for instance) and in school (in this case, state capitals) that you just don’t remember as you get older, until you learn it all again as a parent.

Midnight at the Mani-Pedi

by Lisa Piazza

followed by Q&A

At the Midnight Mani-Pedi they keep the lights dim. This way you can slide your shoes off, ease into an open spa chair, and close your eyes while the hot water and chemical bubbles soak your soles clean. The flashing neon sign outside turns the lady red/now blue as she shuffles over. She is older than your mother. She has worked a full day and then some, but she still smiles as she puts down her plastic supply bin and asks your name. Wants to know which color? She holds out four pinks, none just right. You like the pearly ones best. A little sheen. But tonight you’ll have to live with “Pink Me Up!” You don’t even have enough cash to leave a decent tip.

At the Midnight Mani-Pedi they let you stay as long as you like. This way you ride out the hours till Greg leaves for his 4 a.m. shift at the bakery. You can’t sleep in the same room with him anymore. His breath—textured bursts of weighted air—leaves no space for your own.

The woman next to you is snoring. She is heavy around the middle with blond-gray hair pulled back in a loose bun. She inhales deeply and exhales in long, peaceful streams. It makes you happy in a sleepy way. She reminds you of your second grade teacher. The one you invited over without telling your mom. That was at the little place in the hills, where your mom had a friend who raised goats and traded rent for taking over the goat-care, expecting goat cheese, goat milk, goat yogurt out of the deal. Your mom got pretty good. She lived in a small section at the bottom of the house. One room, really, but there was a side area with a loft bed for your weeks with her.

The woman next to you is in baggy black pants and a fuzzy sweatshirt—too sloppy to be Mrs. Fahy, who showed up to your mom’s in a long corduroy skirt and tight turquoise sweater that matched the sea in her eyes. You saw her from below, holding firmly to the steep railing as she climbed the thirty-two wooden steps down to the first landing in her tall brown boots. You loved the sound of the soft leather folding. Here she still looked elegant. You waved and she smiled and your mom—in garden clogs and jeans—looked up from one of her projects.

“So these are the goats!” Mrs. Fahy said. She asked your mother if she needed help with the meal. You knew there was nothing cooking, but your mother said “Sure,” and led her into the small studio. She was good at going with the flow. Somehow food appeared on the table and you sat down between Mrs. Fahy and your mother who talked together fine. After dinner you told Mrs. Fahy about the Switch Witch who had taken all of your Halloween candy but forgotten to leave you a gift in return. For three nights now she had left you little notes—not exactly apologies, but close. You were hoping for one of those expensive dolls your friends had. They came with outfits and accessories and each one had a story and a pet to go along with it. “Maybe tonight,” you said and Mrs. Fahy smiled.

When the cat walked in through the open window, Mrs. Fahy blurted: “You’ve got to be kidding!” It was only Ruffles, but to Mrs. Fahy, it was a British Blue, the kind of cat her parents raised to show. They had over twelve ribbons. “Best breed in the world,” Mrs. Fahy said. “But they need attention. Care.” Ruffles had belonged to a neighbor at your mom’s last place. When they moved, they had to leave Ruffles with her. Typical of your mother to turn a show cat into a raggedy outdoor mouser. She used to say: “All animals need fresh air and foraging; kids, too,” so you spent hours exploring the hillside property, following Ruffles or wandering on your own.

By May, when the cat disappeared, your mother was looking for a new place to live. She was tired of mud. The sour stench of goats. Your mother said it must have been the coyotes. “Can’t you hear them howling at night? The laws of nature are mysterious,” she said. When you told Mrs. Fahy she put her head down and cried. You cried, too. “Something like that was bound to happen,” she said.

At the Midnight Mani-Pedi they let you haul out the old stories. Spread the facts around or jumble the deck to make a new version. Bookend the moment with an opening scene—a resolute image on the fade-out. This way you can ignore Greg’s latest digs. That’s how you picture it now: him with a big shovel hollowing you out. You like to come here in the hours just after. That is the softest time. When sound slows to a silence. Seconds, minutes, hours squish and merge so that you are in all places/no place at once. Light shifts to prism pieces, then flattened edges—one dimension fading fast.

The Midnight Mani-Pedi is here to fix you up!

Clean feet, polished toes. A little “Pink Me Up” goes a long way.

Let it be Mrs. Fahy beside you. Let her invite you over. Her house is the bright yellow one around the corner with the low palm trees and colorful grasses. All times of the year that garden looks good. She has a pot of minestrone on the stove. She wants to teach you how to draw perspective. Which lines form walls, which angles open windows. She wants to braid your hair. She wants you to sit by the fire and read through her pile of Vanity Fairs. After these thirteen years, she has rescued Ruffles. The cat is waiting, asleep on the couch. You will send a note to your mother in Ireland tomorrow.

This is the way it should go.

Don’t you know the Midnight Mani-Pedi loves you? Says so right there in flashing neon. Loves you on and off all night. You have learned to time your blinks so the love is always lit.

Lisa Piazza runs writing workshops for children and teens in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her work has appeared in Fraglit, LiteraryMama, Rivets and Switchback. Her first story for young adults (published in YARN this past Fall) was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this story?

A: “Midnight at the Mani-Pedi” comes from a fantasy of wishing an all-night salon existed so that after my young daughters fall asleep at night, I could slip into a waiting pedicure chair and rest my feet awhile. If you know of any such places, let me know.

death comes in threes

by Makalani Bandele

followed by Q&A

the drapes thin and light as gauze, caught in a breeze

cause me to look away from the white desert

in her mouth. something, someone approaches.

a little blood trickles from the left nostril, then

a sigh that could be lungs crashing together,

or storm-swollen sea against the pier.

—mother has died singing

how her breasts and hips still remember things

she told herself to forget—

i think i know the song—

try to finish it.

*

how easily the past can overtake the present

if you are not watchful. and if it does,

you walk backwards through the days

with her fears as your only companion.

—i saw it all from my belly, by turns: a whodunit (and why),

a memory, and something of a ghost story.

he died out of his stomach. the silt had built up,

rock had fallen, no one knew it was cavernous

under there. it was where his emotions, especially the grief,

went to hide. he had no respect for the dead,

but wantonly walked in their way, on the shining path,

instead of close and along the wall leading into the town.

all we have left is the pictures of his stomach.

*

after that, i was always by the waters

picking up eggs i found lying around from birds and fish.

i put them inside of me, called myself ark

and stowed them in my womb.

i said to them, i have room for all of you.

Makalani Bandele is an Affrilachian Poet and Louisville, KY, native. He is the recipient of the Ernest Sandeen Poetry Award and a fellowship from Cave Canem Foundation. His poems can be read in various online and print journals. Hellfightin’, published by Willow Books in October 2011, is his first full-length volume of poetry

Q&A

Q:What can you tell us about this poem?

A: I had a vocation as a pastor in two Baptist churches in North Carolina some years ago before I came back to writing. In that time I saw a lot of sickness and death. I performed many, many funerals. There was a saying among churchfolk that I pastored, “death comes in threes.” It related to the strange phenomenon of people dying in sets of threes. A person would pass away, and within a month to six weeks two more people would die, then you might go a year without any deaths in the church, but once somebody died, it seemed without fail two more would die not long after. The poem is simply three vignettes by the same speaker detailing the death of her mother and the attendant grief that drives her brother to his death and her to hers.

Man on the Moon

Terry Kennedy

followed by Q&A

Like the ending flourish of that piece by Shostakovich that she loves but can never recall, first one, seven, then the rest of her guests descend the steps where she sits, her head all vibration, the spin of the party still moving through it. The darkened windows across the street pull her in as she warms to the light of the arching moon, leans forward, tries to hide in the fog of her winter breath—and yes, she is in love with him, and no, he does not know it—and he stares through his window at the moon’s slow ascent, its deep bruises and scars, and the stars pop on, flicker, tease the dark—the streets slowly draining until the hum of the night bus, empty on its route, seems normal, as natural as breathing—and for a moment they are together in this clarity of desire. But this is not that, this is loneliness: the moon taking root in the sky, silence in silence, the stars, and beyond them: ice and darkness—the place where the slow fear of love emanates.

Terry L. Kennedy is the author of the chapbook Until the Clouds Shatter the Light that Plates Our Lives from Jeanne Duval Editions of Atlanta, GA. A new collection, New River Breakdown, is forthcoming from Unicorn Press in 2013. His work appears or is forthcoming in a variety of literary magazines and journals including Cave Wall, from the Fishouse, Oxford American, Southern Review, and Waccamaw. He teaches at UNC Greensboro, where he is the associate director of the Graduate Program in Creative Writing and editor of the online journal, storySouth.

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this piece?

A: The genesis of “Man on the Moon” came during a period when I was suffering from really bad insomnia. When it wasn’t too cold or raining, I would talk walks around the College Hill neighborhood. There were these two houses, across the street from each other, and they always had the same lights on–one upstairs and one downstairs. At some point I began to start imagining the lives of the people in those rooms and what types of relationships they might have.

What an Aunt Knows

by Stephanie Reese Masson

followed by Q&A

It’s hard to find a good stick. It can’t be too short or curved. It can’t be too thick or too thin. It has to be one solid twiggy piece. You can’t poke a dead squirrel with just anything.

He’s only three, but even he knows some of this.

I play stick inspector as he runs around the yard trying to find just the right one. Not the one with branches growing from the sides, not that curved piece of crape myrtle bark posing as a stick. A crape myrtle branch, though, is a different story. It has the right heft and is straight as can be. I approve it instantly.

The dead squirrel in the middle of the road was treat enough, but a poke with the stick took it to a whole new level.

A look at the fresh carcass was the reward for a backyard haircut that he had tried hard to avoid.

“It’s not even a big deal,” I said, when he first began to squirm beneath the old white sheet serving as a smock. “It’s not really anything at all.”

Then as he scrunched his eyes and tensed before his grandmother’s scissors even touched his neck, I pulled out the big guns.

“Do you want to see a dead squirrel in the road,” I asked quietly.

That got his attention. I knew it would. I had to add a message to the grotesque.

“He probably tried to cross without looking. He didn’t know not to play in the road.”

“You shouldn’t do that,” he said, the haircut almost forgotten.

I smiled a little because it worked. I drew out the fun by telling him he could find the stick.

You don’t throw a good stick away once the squirrel poking ends. A good stick serves many purposes. Its next job is to poke its way into crawfish holes. He calls it “fishing for crawfish.”

We walk slowly around the lawn looking for the gray chimneys that signal a fresh mound. The lawn is large and has several areas that stay damp, good crawfish habitat.

Nothing but a nice straight stick will do the job of probing deep into the holes. Sometimes you can touch the water, but if the hole curves, you only hit the side.

When nothing comes up the hole, it doesn’t stop the fun. New holes pop up in the lawn every day. You never know when the stick might come in handy.

It also feels good in the hand. The right stick could swish slowly as you walk around, or make a whistling sound if stroked quickly from side to side. If you hold it just right and swing it really fast, you can slice the tops off Dallisgrass growing above the shorter lawn grasses. I demonstrate and he watches. I never get the stick back after this. He practices over and over. Swish, swish.

Before long it’s almost dark. We’ve spent the whole evening with the stick. Sometimes a good stick trumps TV, technology, and toys.

A stick can become so much more than a stick. An aunt like me knows this.

Stephanie Reese Masson’s nonfiction has appeared in Word Catalyst Magazine and The Battered Suitcase. She has authored academic articles for the MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching and Louisiana English Journal. She also writes newspaper columns on health and wellness. She received her B.A. in journalism and M.A. in English from Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, La. After 14 years in the newspaper industry, she is now an instructor of English and Mass Communication at NSU.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: What surprised me the most about this and other recent stories is how they flow from some unconscious place. I think about things I experience and turn them over in my mind, constructing beginnings until something feels right. When the first sentence or sentences congeal, I feel ready to write, and often don’t stop until I have all the details down. I have no idea why sometimes the stories are there and at other times not. I am also surprised by the depth of feeling and connection I have with my nephew and how often he becomes the catalyst for my strongest works.

Honesty Laid Bare

(A Lyric Essay on Writing)

by Sara Whitestone

followed by Q&A

I write to overcome. I write to become. I write for those who will come.

Since “a prophet is not without honor, except in his own country,” a passionate, articulate writer should not expect full acceptance of (or even always interest in) her work.

Through that freedom of not worrying about what others close to us think, writers are then able to make connections with strangers, those we may never even meet.

I write so that I can bring those strangers, those whose names I will never know, “food, and medicine, and kinship.”

I do this by writing my truth—the truth that I have experienced—because there is no “true to what really happened.”

If I don’t remember this—if, out of fear of others’ anger, I pull back—if I don’t “spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time,” I am no longer being honest with myself or with anyone else.

That honesty—the act of being true to myself—is what makes my writing authentic.

It is what my readers—those strangers somewhere out there—are hungry for.

I write to feed others because, I, too, have been fed. I, too, have found kinship.

Although he never even knew my name, a memoirist once unclothed me through his “pain and longing and adoring”—his “bare branches against the stars.”

Writing is nakedness shared with strangers.

Every day I have two choices:

to run to safety, to cover myself, to hide and to fear

or to stand in the uncertainty of faith, to open myself, to trust and to live.

But what if—in all my honesty laid bare—my truth never nourishes others?

I will write.

Even if nothing is ever even published?

Yes, I will write.

I was eight years old, forming my first fable about why a robin’s breast is red when I understood—understood that “I’ve just got to write. I can’t help it. . . . There are those who must lift their eyes to the hills—they can’t breathe properly in the valleys.”

Forty years later, I am still climbing. I am still writing.

Because I am writing for myself. Finding ways to breathe.

How can I make sense of the past, unless I build some structure into its telling, unless I infuse meaning into its chaos, unless I turn its torture into wisdom and its burning into passion?

How can I be fully alive in the present? How can I welcome the future with faith instead of falling away in fear?

I open my eyes at 6:30 a.m., and look out the window at those bare branches against a dawning sky, hoping, again, that beauty will give me courage because

I am afraid.

I close my eyes, trying to sink back down into the fog of my dreams because

I am afraid.

But my writing won’t let me rest. It rises with the daylight, hardening to full clarity.

By 7 a.m., I force myself to throw back the covers, exposing myself to the cold.

You only have to write a few lines, to bare your truth for only a few moments.

It is 10:30 a.m. I have forgotten even to eat breakfast in the exhilaration that comes with creation.

I am naked, but I am not afraid.

I am not afraid because there is “ecstasy in paying attention . . . where you see in everything the essence of holiness, a sign that God is implicit in all of creation . . . an outward, visible sign of inward, invisible grace.”

And so I pay attention. To what I want to overcome. To what I want to become. To what I want to share with others who will come.

And while I am crafting those truths that I see, I feel that invisible grace breathing into me.

Works Cited

“A prophet is not without honor”

Matthew 15:7, New King James Version of the Bible

“food, and medicine, and kinship” and “true to what really happened”

Lockhart, Zelda. “Freedom and Power: A Talk with Zelda Lockhart.” North Carolina Literary Review 21 (2012): 209. Print.

“spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time”

Dillard, Annie. The Writing Life. New York: HarperCollins, 1989. Print.

“pain and longing and adoring” and “bare branches against the stars”

VanAuken, Sheldon. A Severe Mercy. New York: Bantam Books, 1979. Print.

“I’ve just got to write. I can’t help it. . . . “

Montgomery, L.M. Emily of New Moon. New York: Bantam Books, 1993. Print.

“ecstasy in paying attention . . .”

Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird. New York: Random House, 1994. Print.

Sara Whitestone is a writer, photographer, and teacher. In exchange for instruction in English, her international students introduce her to the mysteries of the world. Whitestone’s creative nonfiction, articles, interviews, prose-poetry, and photo and travel essays have appeared, or are forthcoming, in The Piedmont Virginian, Literary Traveler, Summerset Review, The Winchester Life, North Carolina Literary Review, BootsnAll, Wilderness House Literary Review, and many others. Whitestone discovers writing through travel, and her current work-in-progress is a literary thriller set in Europe that is inspired by true events.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: I wrote this essay all in one long day, alternating between excruciation and exhilaration—between the words on my laptop and the mountain views from my deck. I was surprised at how much I needed to breathe deeply, to let fear rise, so that I could feel all the emotions—the fullness of what I wanted to create.

When I showed the final version to a writing colleague, he said, “In this piece, you have a very interesting combination of rawness and craft. I think that is maybe one of the keys to your writing style and voice: the nerves are scraped bare, with a very elegant scalpel.”

And isn’t this exactly what writers do each day? We take our pens as if they were scalpels and scrape until we hit a nerve. Then, and only then, are we satisfied with the honesty of the work.

Prime Decimals 31.3

Sensory Research

by Maryann Ullmann

followed by Q&A

We serious writers huddle in the corner of the Grand Ballroom at the Hilton. The rest of the conference-goers herd on to the next panel in the next ballroom. But we detain ourselves in commitment to our craft: literary hipsters and aged nerds with berets and sweatpants under the opulent chandelier. We are ready for the experiment.

We had been discussing the importance of sensory research, of going beyond the books. “My protagonist is a vorarephile, a man with a cannibal fetish,” the thirty-something in the tweed flat cap and gray hoodie had said. “And I’m having trouble finding an access point into his psyche.”

“You mean he gets off on eating people?” asked an author on the panel. He had published three novels set in Indiana.

“Not so much. More, he gets off on being eaten. It’s for real, this desire to be devoured. It exists.”

“I don’t doubt it.”

“Maybe,” suggested the flat-cap guy, “if it’s entirely consensual, of course, if anyone’s interested in trying it out, I mean, we could all write about it after, what it’s like, to be eaten, to eat flesh, to witness the act, whoever’s interested, you could meet me in the corner after, over there,” he pointed to the spot away from the windows, where painted Victorian ladies sipped tea in soft lighting.

After, now, we stand over there, waiting for something to happen.

“This is ridiculous,” I say. “We’re not going to go through with this. We’re writers, not sadists.”

Others nod. We make to leave.

“Wait,” says the flat-cap guy. “I’ll do it. I’ll be eaten. We’ll start slow. We’ll start with a sliver off my pinky. Would anyone like to, dare I say, eat me?”

We giggle; we look around.

“I would,” squeaks the graying curly-haired woman in the pink scarf. We’ve seen her in other panels, espousing her affections for Virginia Woolf and Alice Munro.

“Brilliant,” says the flat-cap guy. He sends a Hilton attendant to fetch a sharp knife.

He grows excited. “If anyone finds themselves sexually aroused by this event, even slightly, at any given point, please do let me know.”

The attendant returns and the flat-cap guy flinches at the shining blade, but grips it in his palm. He holds it to the end of his pinky like a paring knife, like one might peel a narrow carrot. We wonder if he might be a chef, the way it’s poised. In the quiet, we watch his hand shake. He whispers to it—“Stop”—like he’s cooing to a scared kitten. His hand obeys and slices the knife down. The fresh red bubbles up and we all lean in, mouths agape like women applying mascara. He glides the knife along the edge and narrates the experience for us. “It stings,” he says. “And the skin wants to cling. It’s not so easy, breaking it apart. The flesh is alive.” He manages to pull a sliver free and hands it, wriggling like a minnow, toward the woman in the pink scarf.

Her mouse eyes do not widen, but focus tightly on their task. She takes it and holds it over her outstretched tongue. A few of us turn away and cover our mouths. We hear her say, “It’s salty. It’s warm. It’s like a microwaved rose petal. It’s slightly creased like the sea.”

“I’d like to try,” says a young man with a red goatee.

“I might be getting aroused,” says a girl in a vintage cardigan.

The woman in the pink scarf is still chewing, her eyes closed; a twitch of her lip betrays a moment of registered disgust.

That it’s difficult to pry myself away unsettles me. More so, that I am the only one who does.

Maryann Ullmann is a Whitford Fellow and MFA candidate in fiction at Chatham University in Pittsburgh. Her writings appear in Permafrost, Halfway Down the Stairs, Cultural Survival Quarterly, and Whole Terrain, among others. She traipses around the globe with an imaginary llama named Svenz who feeds on alfalfa and dulce de leche, her most stable home at www.maryannullmann.com.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this piece?

A: This piece was inspired by a dream I had following the Midwest Gothic panel at AWP Chicago. In the dream version, I was about to eat a sliver off my own finger, but woke up just in time.

2 Stories

by Pete Stevens

followed by Q&A

Never Never

watched as my brother was consumed by flames. Mother told me to open a window. I did. The smoke, tiny particles of my brother, rolled out the kitchen window like nobody’s business. Mr. Swanson (kids called him “Swanny” or “Dickface”) always said “nobody’s business.” He was also fond of “ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” both of which seemed appropriate. After my brother finished burning up, I crawled out the window to see where he went. I found him perched in a tree eating peaches from a paper bag. He called me a wanker and threw a pit from high above. I imagined I was a jungle cat and began to climb the tree. Anyone watching would have to admit I climbed like nobody’s business. At the top, I discovered my brother had gone. I looked across my neighborhood, at all the trees like mushroom clouds against the horizon. Mr. Swanson said the world would soon end at the hands of a madman. Sometimes, at my window, I’ll see the bomb blasts getting closer and closer, pillars of smoke rising tall in the sky, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Niccolo de Quattrociocchi

ake sixty-four blank business cards. Find sixty-four lovely ladies, sixty-four different shades of red lipstick, and have these lovely ladies plant a fat red kiss on each card. Arrange the sixty-four kiss-smacked cards in a square grid, but tilt each off its axis just so. Give the impression of nonchalant splendor. Now take your eight-by-ten glossy of Niccolo de Quattrociocchi, the one with Niccolo sporting a smile and a sharkskin, the one with Niccolo’s razor-sharp mustache, his soul-piercing eyes, and lay it on top of the red-kiss grid. See the kisses surround Niccolo. See the kisses dance and flex and swirl around Niccolo with something like love. See these sixty-four kiss-smacked cards as representations of the sixty-four heartbreaking beauties that came and passed through Niccolo’s life. Know there was a sixty-fifth. Know this woman, Clarice, took our Niccolo’s heart, placed it in her purse, and boarded the first flight back to Sicily. Niccolo was broken, void. He searched for his heart in the subway, on the pier, he looked behind locked doors, but Niccolo de Quattrociocchi was luckier at roulette than at love, and his heart was never found.

Niccolo, or Nicky Q to his friends, spent a life of luxury and sophistication. Trained at an Italian nautical school, Nicky Q found his way to America, to the land of opportunity. He found work walking dogs, sculpting bridal couples for wedding cakes, making pretend love to Pola Negri on the silent screen, and finally, as a gourmet chef for New York’s elite. Soon, Niccolo was the owner of El Borracho, the pinnacle fine-dining experience in all of Manhattan. Here was a man women swooned for. Here was a man with ravioli that melted in your mouth like a puff of cotton candy. And yet, here was a man of regrets. He was a man with a misplaced heart, a heart back in Sicily with his sixty-fifth, Clarice. No, Niccolo would never forget. He died alone. He died with a hole in his chest. He died with a photo of himself in his hand, the one taken by Clarice, the one where Niccolo was content, the very same one you placed on your kiss-smacked grid. Now take those sixty-four red-kissed cards and throw them high into the sky, let them flutter and spin and fall down around you.

Pete Stevens is the Fiction Editor at Squalorly. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Cardinal Sins, The Legendary, 101 Fiction, Eunoia Review, Literary Orphans, and elsewhere. He lives in Bay City, Michigan.

Q&A

Q: What inspired these pieces?

A: With “Niccolo de Quattrociocchi” it started with a food memoir, Love and Dishes, by Niccolo de Quattrociocchi that my girlfriend, Rachel, picked up at a downtown Detroit used bookstore. On the back cover of the book there’s a picture of the author surrounded by these cards with lipstick kisses. When I saw that image, the look in his eye, his smile, I just had to do something with it, I was captivated. I knew my job was to tell Niccolo’s story in my own, postmodern, twisted sort of style.

With “Never Never” it started with the first sentence. I walked around with that sentence for days, weeks, waiting for the right inspiration. It seemed, no matter what I did, I couldn’t get away from all the doomsday talk in the news. So I decided to write a piece that explored the way a child’s imagination might react to all these end of the world concepts that they might hear from teachers or other adults. And I wanted the imagery of the piece to reflect the vivid imagination of a child.

Solitary Vireo

by B.J. Buckley

followed by Q&A

Though I know the music of this vulnerable world

is not an orchestra nor any bird mere instrument

the sweet deliberate tuning of your impudent

violin, vireo, bow of instinct, song

from the lacework of new leaves: out of the hollow

of your bones, melody – though I cannot see you

hidden in the green. Or your polished wing, brink to

branch taut sail trimmed to the wind; nor nest

a little loose and pendant from a slender fork,

resplendent: wasp paper, strips of bark, egg case and silk

of spider, blue or yellow shred of envelope (a fragment

of lost word) – lost world today I cannot mourn

for you’ve eluded cat and Cooper’s hawk,

barnstormer bob and dip, and the abyss,

that nothing opening beneath, to you

is nothing – cloud broom, swept space of sky,

hawks hung soundless golden in the blue

in seeming contemplation of the infinite. Below,

neglected garden, hellfire orange poppies

bowing to your antic flight, your pizzicato

call, quick trill and tremolo for the female

brooding on her nest: Four eggs, oval, pointed,

creamy white, sparse spotted black and brown,

smooth-shelled without gloss. Within

a choir, quartet of tiny strings:

chamber music, ripening.

(Note: information on the nests and eggs of vireos from

Petersen’s Field Guide to Western Birds’ Nests, 1979,

by Hal H. Harrison; and my own field experience)

B.J. Buckley is a Montana poet/writer who has worked in Arts-in-Schools/Communities programs throughout the west for over 30 years. She is currently Writer-in-Residence for Sanford Arts at Sanford Cancer Center in Sioux Falls, SD. Her poems have appeared widely in both print and on-line magazines, including Cutthroat, The Cortland Review, Big Sky Journal, Green Mountains Review, Visions International, Up the Staircase, and Mezzo Cammin. She is the 1st and 2nd Place Winner of the 2012 Comstock Review Poetry Prize. Her letterpress chapbook, Spaces Both Infinite and Eternal, is forthcoming from Rick and Rosemary Ardinger’s Limberlost Press, Boise, ID.

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this poem?

A: I’m most happy outdoors, and have had many opportunities to observe birds and wildlife in the areas of rural Montana where I’ve lived. This poem emerged out of fascinating multiple field observations of a solitary vireo pair and their nest over the course of an entire season, coupled with my frequent consultations with field guides and fellow bird watchers. Fall winds eventually brought down their nest, so I was able to examine it closely–a rare privilege!

The Perfect Stroke

Marcia Aldrich

followed by Q&A

Right now everything I am is understood

by the word swimmer.

I am a long way from home, severed from my mother

and that particular history of trouble.

Lonely and not lonely: what swimmers call the zone,

the sum of me concentrated into my stroke.

It doesn’t matter if the water is frigid

or if I am alone or with others, I am complete.

What works for me doesn’t work for everyone.

Some people don’t enter the water and breathe more deeply.

They need to be upright, to hold onto to something,

If you loosen their blankets and free their limbs, they twitch like babies.

But water doesn’t work that way—you can’t bend it.

Subdue yourself. Swim inside the water.

I am not plunged into the darkest of moods

when I read of a young person pulled under in a rip tide

Or trapped under a floating dock.

Water contains a history of drowning in its depths.

The breast stroke is my stroke.

I lie in the water face down,

arms straightforward and legs extended to the back.

I plow my head into the water

the way a beaver ducks under the ice.

Timing is tricky.

For the arm movement, 3 steps:

Out-sweep, in-sweep, and recovery.

Out-sweep, in-sweep, and recovery.

The story of my life.

Usually being a quiet person hurts me.

In the water the quietest person is the best swimmer.

Working against water is exhausting.

I’ve been held under inside a kicking wave

And then spit up and out and back to shore

like a piece of sea kelp whose holdfast failed.

If my life had a title, it would be Inside Water.

A fraught birth, drowning, attempts at rescue, a raft,

Corpses borne on a current, funeral bier at sea,

Resurrection.

No one’s a child anymore.

Sometimes when I’m waiting for a lane to open up,

I watch the other swimmers going up and down

The lanes at the exact same pace, using an unvaried stroke

As if a giant metronome ticked in the sky above us.

I’m far out and no one is paying the least attention to me.

I might be invisible.

I’m swimming on my back looking up at the sky.

The song that I sing is so beautiful that sometimes it breaks me.

It is a small song, a mere echo in the vast empty room.

Marcia Aldrich is the author of Girl Rearing, published by W.W. Norton and part of the Barnes and Noble Discover New Writers Series. Companion to an Untold Story, selected by Susan Orlean for the 2011 AWP Award in Nonfiction, came out in September 2012 with The University of Georgia Press. For further information see:marciaaldrich.com

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this poem?

A: I conceived of “The Perfect Stroke” as the final piece of writing I would do on swimming. I was wrong and have since written two more pieces. I have a history with swimming and a history of writing about swimming and I hope I’ll never exhaust what swimming means to me. In this instance a quote from Keats provided inspiration. “The point of diving in a lake is not immediately to swim to shore, but to be in the lake. To luxuriate in the sensation of water. You do not work the lake out; it is an experience beyond thought. Poetry soothes and emboldens the soul to accept mystery.”

Three Tons Wait

by Lara Dolphin

followed by Q&A

On my mind this morning is rubber, a lot of rubber. Last week the swing set we ordered for the backyard arrived in two large boxes that now sit on the porch. My husband and I, on track to be parents of the year, are investigating what, if anything, to put under the monstrosity to protect the kids from falls. Back when I was little, my sister and I rode our swings into the stratosphere over the concrete in the breezeway of our parents’ house. We never broke a bone though we stood on the swings and did all manner of tricks. Still, today things are different. The kids ride in car seats, then boosters; our baby sleeps on his back not his belly and the water in our house never heats above one-hundred-twenty degrees. In the world of playground landscaping, the gold standard in safe surfacing is rubber mulch, which is currently used under the White House playground.

Made from environmentally friendly recycled tires and ninety-nine percent wire free, the rubber mulch is available in a rainbow of colors from earth toned brown, to eye-catching red, to shock-the-neighbors blue. Having done my research online, I place a call to the company to find out more. Someone named Julie tells me that the mulch arrives in two-thousand-pound bags. “Based on the dimensions of your playground,” she says finishing the calculation, “I would recommend three bags.”

“Where do they leave it?” I want to know.

“They deliver the mulch to the end of the driveway.” She says that we’ll want to make quick work with a shovel once we see the pile looming in front of our house. “Three tons of rubber mulch is very motivating.”

Undeterred, I wait while she calculates the cost. The gobsmacking quote she finally gives me turns out to be five times as much as the cost of the playground itself and convinces me that woodchips or even grass will suffice. When I recover from the shock, I thank her for her time and hang up, but not before devising a motivational theory, namely—a job once started begs to be done.

***

Since the birth of our third child two months ago, time is a stonkingly hot commodity. With barely two minutes to rub together between feedings, diaper changes, and looking after the older kids, I am on a perpetual quest to squeeze extra minutes from the day. A dab hand at list making, I tried that approach. I gave it up, though, when I came across a list reminding me simply, “Eat.” Armed with a new theory I decide that I will approach tomorrow by starting a bunch of tasks, completing none of them, with the hope that, by end of the day, the sheer cataclysm that surrounds me will motivate me to complete the chores.

The next day begins full of promise. With the morning mayhem over and all but the baby safely on their way to work or school, day one of my experiment in slapdash living begins. I make an imperfect attempt to fix my hair in the rear view mirror, and then head into the house. I deposit the baby snug in his car seat in the first floor laundry room. I start the dryer for background noise and close the door. If all goes according to plan, I have an hour before he wakes for a feeding.

After a quick call to the prothonotary’s office to check on passport processing hours, I dash around the house starting half a dozen small tasks. Up goes the lid on the coffee maker reminding me to make tomorrow’s brew, which my husband will drink and I will not. The sheets come off the beds, though there is no time to put new ones on. Dental floss comes out of the drawer and onto the counter, and scolds me for forgetting to floss the kids’ teeth yesterday before bed. The manual for the car seat hits the same counter, reminding me that the baby’s five-point harness needs to be adjusted. The broom comes out of the closet hoping to be a guitar or a horse and play rock star cowboy with our son. Instead, it reminds me of the unswept crumbs carpeting the kitchen floor. I am going full steam when the phone rings. It’s my husband calling from work. I provide a recap of the morning so far. “You sound like you’re on speed,” he says.

“I’m getting a lot done,” I say. So far, I’m half right. The house alarm starts to sound. “Got to go.” The keypad sends out a warning. “Zone 28. Low Bat.” I disable the alarm, and then head for the kitchen. I grab fresh lithium batteries from the freezer and put them on the counter. Then another sort of alarm goes off. This signal is coming from the laundry room.

“Hold on, Henry. Mommy’s coming.”

***

After a diaper change, we settle into a comfortable chair for the midmorning feed. Holding my baby’s small hand in mine while he nurses, I remember my grandfather. His hands were wide and strong, befitting of his name, Peter, “the rock.” A decorated military hero, college graduate, salesman, and family man, his hands were forged through years of combat, study, work, and sacrifice. I remember how he clapped his hands when he laughed, how he rested his bent head on them when knelt in prayer, or how he’d make a point in Italian to anyone who would sit awhile. Most of all I remember, when his legs were going numb and he could barely stand, taking his hand for support and surprised by his strength.

After months of battling pneumonia and kidney failure in an intensive care unit, he died the day after Henry’s birth. Still, exhausted and elated from the delivery, I got the call in my hospital room. Unable to go to the funeral, I find it hard to comprehend his passing. Today, after feeding Henry, I place him in the bassinet and head up to my room for a moment. I take my rosary from its drawer and put it on the night table. When I can, I will say a novena for my grandfather, il mio caro Nonno. Until then, the beads will remain, a reminder of my unfinished work.

Then, when the time comes, I will feel my grandfather’s loss like a three-ton weight on my heart.

Lara Dolphin is a graduate of The University Notre Dame and The Dickinson School of Law. She practiced for four years as an attorney. She now spends her time writing and refereeing four kids.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: I was surprised that the process of writing about the death of my Nonno created in me some inner space in which to hold his memory.

The Idle and the Blessed

by Natalie Parker-Lawrence

followed by Q&A

"I do know how to pay attention . . . how to be idle and blessed . . ."

Mary Oliver

We rumble past signs: Esso Mecanico! Servicio Technico! Every few dry kilometers along the highway, we pass faded buildings with patched and abandoned beginnings of compound courtyards: cement block, corrugated metal, graveled rocks, painted aluminum, brown stones, graffitied advertisements. Those who erect these walls leave for reasons we cannot imagine. They are undone.

Esso signs proffer gasoline when our bus breaks down among pink-washed houses with blue windows.

In Central Mexico, we writers come from everywhere but here.

We let slip the sweaty dogs of summer. We wander.

Two kinds of cactus, those with spikes and those with spires, compete with the flesh-plowed fields, no cactus, only the promise of corn. But in the sparse orchards, planted long ago, cactus thrives; the needled shrubs grow even if no one plants them, specious protection like a hedgerow.

Factory smoke, like molé, rises from fifteen chimneys, no attention to filters or regulations, blowing hundreds of miles, dropping its thick brown heaviness on crops and lakes on its way to the ocean where it rains into the sea and ascends as wooly clouds over Cuba.

We step over old women, squatting on the rough steps outside the fleck-chipped door. We turn our heads to avoid the searching faces that could belong to our own grandmothers. We whisper that there, but for the grace of god, go we. We hurry through the blue door to buy rolls.

Men hold babies and bicycles, waiting after school for sweet big-eyed faces. Perhaps their parents hide the ugly children the way we do in America. We hide tiny white coffins. They pile them high in their storefront windows next to the dress shops.

One three-year-old boy plays with a raw egg on the earthen floor of the market. The only toy anywhere around him; the yolk breaks and commingles with dirt-straw. He stirs it with a stick from a spindly tree. He sings.

The old women cook gorditas filled with barbacoa. Their hands fold dough over a pinch of goat or pig meat. No one offers the salty coolness of avocado bisque or ochre fritters made of squash blossoms.

Soft mountains, worn down by wind and by oceans and by war and by mining, lean over the old man and his plow, a thick metal blade, cutting through the parched desert earth with his strength and his horse cabled to his gray-sand donkey.

They are the ants.

We are the locusts.

We pay a dollar for a lunch that costs eight bucks 1,200 miles from here.

We unhinge our jaws to complain about heat and dirt.

We gorge on cold guacamole.

We ride in a bus with a movie, chilled air, and matching tires.

We borrow street anguish as inspiration to increase our page count.

We wash the stories down with shots of vodka in a country that grows no potatoes.

Natalie Parker-Lawrence earned an MFA in creative nonfiction and playwriting at the University of New Orleans. Her work has been published in Slice of Life Magazine, The Barefoot Review, The Palimsest Journal, Stone Highway Review, The Literary Bohemian, Knee-Jerk Magazine, Tata Nacho, Orion Magazine, Wildflower Magazine, Edible Memphis, The Commercial Appeal, Alimentum, World History Bulletin, and The Pinch. She has work forthcoming in The Southern Indiana Review and Uneasy Bones. She teaches AP English literature and AP world history, and is an adjunct instructor in the communication department at the University of Memphis. Natalie lives with her husband in midtown Memphis in a 100-year-old house where her daughter, five stepsons, two daughters-in-law, one grandchild, and one Golden Retriever come and go.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: I am like most writers: our first drafts are golden, brilliant even. But, at this stage we are delusional and caught in our own egos. It took me a year to cut this essay in half because I was certain the reader could not get every turn with the minutiae I had loaded into its mounded and burdened paragraphs. To cut the essay, I had to use new eyes to see what the reader would need as essential information as opposed to what was overwhelming. I wanted to keep the poetic rhythm and the intense details. I wanted to keep the extended metaphors and the themes of social justice. I wanted to keep the speaker’s voice as woven as possible with a narrative rather than too much philosophy, one who learned from her experiences along the journey as well as the people inside and outside the bus.

Prime Decimals 31.5

Beyond Redemption

by Gary V. Powell

followed by Q&A

One summer, my uncle Dewey Henderson, a big preacher man out of West Plains, endeavored to save our souls. Three hundred pounds of self-righteousness and twitchy Elvis lip, my mother’s brother arrived in a finned-out Cadillac, made himself to home under our roof, ate large quantities of our food, and devoted his evenings to revival meetings throughout Northern Indiana.

We sat front row and leaned into his sermons. He railed against fornicators, adulterers, and drunks. Bone into flesh, he derided the idea of monkeys becoming men. False idols and golden calves, he scoffed at the Pope on his throne. At evening’s end, his Bible held high, the sweltering tent ripe with the stench of fire and brimstone, he made his Invitation, calling the sinners and backsliders forth, imploring us to believe and be saved.

espite his pleas, my parents and I sat tight in our uncomfortable metal chairs, as if sin and damnation were beyond our ken.

But earlier that summer, I’d seen my mother kiss another man behind the Top Value Stamp store where she worked, redeeming little yellow stamps for clocks, lamps, and other household items. No friendly peck, this kiss was like a thirsty woman drinking from a mountain spring.

Most nights, after dinner, my father slipped out back with his Seagram’s and Seven, fighting mosquitoes and listening to his St. Louis Cardinals through the KMOX static. When I arrived home late, I’d find him—mouth open, mosquitoes buzzing. I’d nudge a shoulder into his armpit, and walk him inside.

Was the Wenger girl kept me late. While her mom packed vitamins second shift at Miles and her dad roofed RVs at Nomad, we lay naked and damp on their sofa, our legs entwined, our teenage hearts bursting with certainty—we are the only ones.

Believe and be saved, my uncle implored from the pulpit.

My mother fanned with her folded program.

My father ran a wire from his transistor radio up his sleeve.

I lay a songbook across my lap, hiding an erection borne of that Wenger girl.

But the sinners—blackguards, dancers, on-the-sly gamblers, and those greedy in the World—lay down in cool waters. They emerged dripping and clean, gasping and ecstatic. Washed in the Blood and Saved in the Lord.

A lawyer by background, Gary V. Powell currently spends most of his time writing fiction and wrangling a 12-year old son. His stories have appeared at Pithead Chapel, Newport Review, Fiction Southeast, Carvezine, and other online and print publications. In addition, several of his stories have placed or been selected as finalists in national contests. Most recently, his story "Super Nova" received an Honorable Mention in the Press 53 2012 Awards. His first novel, Lucky Bastard, is currently available through Main Street Rag Press.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this piece?

A: I’ve long had memories of attending tent revival meetings. Notwithstanding the preachers’ conviction to the contrary, most of the folks were far from evil, troubled being more like it.

Soft Clay

by Alison Barone

followed by Q&A

er first boyfriend had made a Pikachu sculpture for her out of modeling clay. It was one of his talents. All over the boy’s room were models, the size of children’s action figures, made out of clay. Blank human forms in Crayola “tumbleweed” were laid out like gingerbread men on shelves, on tables, and inside his closet. They wore schoolgirl outfits and tuxedos, sundresses and tunics, and more than a fair share of them were dressed like Alice. He had a dozen Alices in puffy blue dresses and white lace made from clay. Something was wrong with all of them, he said. The first one’s proportions were off. The sixth one’s dress had come out the wrong shade of blue.

he thought he could make money off of them, that he could create figurines of characters and sell them over the Internet to fans. Say you wanted Spiderman or Batman but didn’t want to pay the comic shop’s high prices? The quality was there. But they were too soft, he said. They wouldn’t survive shipping. He didn’t like the sort of clay you bake in the oven. The soft kind could be manipulated again and again. It never dried out, never stuck, never stayed. But that made them unsellable.

The Pikachu he made her was actually a twin. The original was slightly off-color, he told her while she watched. He started over so that he could get it just right. And it was just right. The sunshine yellow body, the cherry cheeks, the lightning bolt tail with a tuft of brown at its base—the whole thing was smooth, devoid of the lumps and fingerprints she couldn’t seem to get rid of whenever she tried it herself. She carried the Pikachu home in a Tupperware container stuffed with Kleenex.

Soon, it collected dust on top of her desk, but she didn’t know what to do with it. So she left it alone, next to her textbooks, and watched over the course of a year as the bright yellow diminished from little grains of grey dust, as the fingerprints of girlfriends—she’d come to learn that she preferred girls—left smudges on the yellow body. But she still found it beautiful the way a good memory stays beautiful even after the person is gone.

One afternoon, cleaning her room, she found that a stack of books had crushed the clay sculpture, smeared Pikachu’s ears and arms all over a biochemistry textbook. She remembered the boyfriend then, remembered the way he’d taken the original sculpture, the one slightly more golden, more orange, than hers—how he’d thrown it against a wall. The toothpick sunk for structure in the tail had snapped and unburrowed itself from the clay. His fingers—soft and small and so much more delicate than hers—when he’d shown her how to do it for the first time, his fingers took on the yellow, red, brown, and black hues until they were smooth, slick as wet mud. He could massage two colors together until they became one, could run his fingers over arms and legs and spine until everything was smooth and electric and yellow. But he’d said he wasn’t done, that this one wasn’t good enough, that he’d start again for her until it was perfect. And it had been perfect. For a month, maybe more, it had been perfect, and then he’d learned about her, about her and her, and the first Pikachu had hit the wall.

Finding the second wrecked, she wanted to cry, but her girlfriend was there, and so she said that it was no big deal, just soft clay. She could always reshape it.

Alison Barone is an undergraduate student of creative writing at the University of Central Florida. She is interested in the fields of fiction and poetry, with a focus on LGBT and gender issues. “Soft Clay” is her first published story.

Q&A

Q: What was the inspiration for this piece?

A: The inspiration for this piece actually came from a writing exercise for class. The assignment was to choose something that you care for deeply, and then imagine its destruction. I have these little clay figures sitting on my desk at home, and thinking about them being destroyed made me feel terrible. I knew that writing about them was the only thing that would feel authentic.

In a photograph of my grandfather

by Claire Hermann

followed by Q&A

In a photograph of my grandfather

he’s flinging his arms wide open,

he’s grinning like there’s never been any moment

better than this,

like he’s been waiting his whole life

for his skin to thin

and his veins to rise

and his strict buzz cut to turn gravel-grey,

for his soldier’s shoulders to narrow

under his smooth golf shirt,

for his wrists to turn fragile

under his gold watch.

He’s grinning like his daughters

were never late for dinner,

like his wife

didn’t vote for Roosevelt,

like he’s her first

and only love,

like his family,

his whole world, is wound

as precisely as his desk clock.

He’s grinning like he’s got only

one war story to tell –

the day he saved the

Roman temple from bombing –

like that’s why he got his silver

star, like he

never stormed a bloody

beach in a slow

boat under fire, like

he never ducked along a low

stone wall while the men beside

him fell, like he never

ran on without

so much as a pause to

glance down or speak

their names.

He’s grinning

like he never

watched bomber after bomber

crash on the runway,

gas gone, landing

strip clogging with

fire and debris and

bodies rolling

like bombs from

the open doors.

He’s grinning

like he woke up, this morning,

in this low, flat-roofed house

by a golf course hung with Spanish moss

in a state with no income tax,

strolled out his patio door,

played the game of his life,

hit a hole-in-one,

came home through the sunny morning,

and here we were in the living room,

with his terrier dog, with his avocado sandwich, on time.

He’s grinning like he won’t forget this,

like his lungs won’t close

and his heart won’t skip

and his eyes won’t gum

and his dog won’t die,

like this day will go around and around

like a minute hand

and he’ll keep flinging open his arms

in welcome.

Claire Hermann’s work has been published in journals such as Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, Caesura, EarthSpeak, and Southern Women’s Review, and is forthcoming in The Wayfarer. When she isn’t writing poetry on her porch in the woods outside Pittsboro, NC, she coordinates communications at a local nonprofit.

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this poem?

A: The gaps between histories—personal, family national—and the stories we choose to tell about them are often places that spark poems for me. I read this one in public for the first time two weeks before my grandfather passed away. The light-damaged, off-center photo that inspired it earned a ticket out of a trash pile and into a frame.

Not Finding

by Charles Wilkinson

followed by Q&A

No registering how

the voice changes

from the inside

though finding it

is what you are

asked to do –

why say that

it’s there, lying

essentially within:

words recovered

from the well of self,

a certain pitch?

If stone catches &

keeps half the voice

it throws back

the loss is here:

its emptiness the sound

absorbed by moss;

the pure flow

of first water’s

singing underground:

a voice without

an echo &

never found:

no need to ask why

searching brings up

the bucket – dry.

Charles Wilkinson was born in Birmingham, United Kingdom. His publications include The Snowman and Other Poems (Iron Press, 1987) and The Pain Tree and Other Stories (London Magazine Editions, 2000). His recent work has appeared in Poetry Wales, Poetry Salzburg, The Warwick Review, Tears in the Fence, Shearsman, The Reader, The SHOp, Envoi, San Pedro River Review, The Conium Review and other magazines; one of his poems is forthcoming in Gargoyle (USA). He lives in Powys, Wales, where he is heavily outnumbered by members of the ovine community.

Q&A

Q: What can you tell us about this poem?

A: Writers are often exhorted to find their own voice or congratulated by critics when they are deemed to have discovered it. Whilst it is obviously an asset for any poet to have a distinctive way of addressing the world, I wonder whether we spend too much time worrying about something that either isn’t there or must inevitably change over time. And what if you have more than one voice or you don’t like your voice when you find it? I suspect that the regularly repeated stricture that a poet has not yet found his or her voice is at best a lazy criticism.

Bee Stings

by Julia Nunnally Duncan

followed by Q&A

Early this May morning, a hornet buzzed around my head and became tangled in my hair while I sprayed insecticide on a rosebush behind my house. I swatted the hornet away and ran from it. But concerned about the bug holes in my rose leaves, I went back to resume my spraying, my hair now twisted and pinned up in a chignon.

As soon as I aimed the spray nozzle, the hornet reappeared and made a swoop at the nape of my neck. I thought it had flown down my T-shirt. I ran to find my husband, who inspected my back and found nothing, but I couldn't take a chance. I went inside his workshop, ripped off my shirt, and shook it. No hornet flew out.

I am afraid of bees, hornets, wasps, yellow jackets—all the stinging insects that seem to inundate our area of western North Carolina.

Last September, my husband stood near a hummingbird feeder that hung from a maple tree limb in our front yard. A large hornet was chasing away the hummingbirds that were trying to drink nectar. When my husband stepped too close, the hornet made a beeline for his right arm. I stood on our front porch and saw him swat at his wrist.

This was not good. A couple of years earlier on an August evening, he'd been mowing grass around the perimeter of our vegetable garden when his lawn mower ran over a yellow jackets’ nest. In a few seconds, he'd been stung several times on his arms and chest. He shrugged off the stings, planning to continue mowing. But I noticed that a sting on his chest looked oddly red and more swollen than the others. I told him to come into our house, where I gave him two Benadryl tablets. Soon I saw puffiness under his eyes, swelling in his upper lip, and red blotches on his chest.

“I think we need to take you to the emergency room,” I said.

Surprisingly, he didn't argue, and as we raced the twenty-minute drive to the hospital, his eyes continued swelling almost shut, and he complained that he couldn't breathe.

At the entrance to the emergency room, an orderly came out to my Jeep. I told him our situation, and a wheelchair was rushed to the passenger door.

Once he was rolled inside into an examining room, a nurse started an IV of fluids, injected him with epinephrine, and followed up with a corticosteroid shot. For an hour, she monitored his oxygen level, blood pressure, and pulse. An attending physician checked him periodically until his swelling and hives were gone and his vital signs normal.

“Try not to get stung, even by a honeybee,” the physician warned and prescribed an Epi-Pen, a self-injectable dose of epinephrine to use in the event of a sting.

But we knew we lived in an insect war zone. With thirty acres of mostly untamed property and duties of mowing, brush cutting, and outbuilding maintenance, my husband stood a good chance, indeed, of another bee sting.

I didn't expect it, though, in our front yard at a hummingbird feeder. Last September when I saw him swat at the hornet, I ran and grasped his arm.

“Did it sting you?” I asked, inspecting his wrist. I detected a tiny red pin prick on the edge of his wrist bone.

“I think it just glanced off me,” he said. I didn't see a stinger and hoped, too, we'd dodged the bullet this time.

“Come in the house,” I said, a little uneasy as I remembered the doctor's warning. “Where's your Epi-Pen? Maybe you better use it anyway.”

I found his Epi-Pen in his bathroom and stood at the kitchen table reading the patient directions.

When I went back into the living room, I found him lying on the couch under the spinning overhead fan.

“Why are you lying down?” I asked. “Do you want me to take you to the hospital?” I noticed a slight puffiness under his eyes. His upper lip didn't seem swollen. “You better use your Epi-Pen,” I said and handed it to him.

He said the medicine looked cloudy and might be expired. He felt okay, he said, just nervous. He didn't seem okay, though, not quite lucid.

He looked pale, and I felt his forehead. His skin was cool and clammy, little beads of sweat forming on his brow.

When I noticed his odd swallowing—little short, quick gulps—I panicked and said, “I'm calling EMS.”

Why had I waited so long? I would never be able to drive him to the hospital in time.

By the time I reached the telephone to dial 9-1-1, I heard him vomiting in the bathroom.

On the line the dispatcher asked, “Are you with him? Is he breathing?”

“He's throwing up. He's having an allergic reaction.”

Soon the ambulance arrived and rushed him to the emergency room, where again he was treated, monitored closely, and released. The next day he refilled his Epi-Pen prescription. I took a can of wasp and hornet killer, doused the hummingbird feeder, and took it down for good. I knew we had flowers to feed the hummingbirds that would come looking for nectar. The hornets, on the other hand, could find their food elsewhere.

Today is just the 26th of May, and the hornets are on the war path again.

Until my husband's recent bouts with sting allergies, I hadn't been paranoid about getting stung myself. Through the years, I have been stung by hornets and yellow jackets whose nests in azalea bushes or in grassy banks I've happened upon. With no reaction beyond pain, swelling, and itching, I've fared well. Our daughter has also been stung a few times in her thirteen years, but she, too, thank God, has handled stings well.

In my childhood, bee stings were a part of summer life, especially the summer of 1964. Late in the afternoon on the 5th of August, when I was eight, I joined the neighborhood kids on my block as we gathered at my friend Becky's house. We had formed a club and were conducting an initiation that required us to stand on our heads in Becky's sloping backyard. Despite the foam rollers my mother had placed in my hair and my general lack of agility, I attempted to balance on my head.

Immediately, I noticed stinging sensations on my head, neck, and arms. I dropped down, hurrying to get to my feet. By that time, yellow jackets were swarming me.

I started running, squealing, and swatting, and my friends trailed behind me. I managed to get through Becky's back door and into her kitchen where her mother, a nurse, dusted me off, inspected me, and picked yellow jackets out of my ears.

She sent me home to my parents. When my father saw my welts, he said we were going to the doctor's office. But before we left, my mother started filling the bathtub.

“She needs to take a bath before we go,” she said.

My father didn't think this was a good idea.

“She's too dirty to go to the doctor,” my mother insisted. “It won't take but a minute.”

And so I took a quick bath, and afterward my mother took out my hair rollers and brushed my waist-length hair, already curly on the ends.

Dr. Allen, our town's youngest and most attractive doctor, amiable and not prone to giving penicillin shots, greeted me with, “Hello, Blue Eyes. What happened to you?”

He didn't seem alarmed when I told him, just curious and a bit amused. He checked my stings and prescribed a salve.

This incident didn't stop me from playing in Becky's yard or from doing anything I'd always done. For the rest of that summer and in the summers to come, I trod barefoot through clover-filled grass, alive with honeybees. Occasionally I stepped on one, its stinger left in my foot. Sometimes my foot swelled so large it wouldn't fit into a shoe, a flip-flop barely sliding on. But immediately after the stinger was pulled out, some woman—family member or neighbor—would stick her forefinger under her bottom lip and scoop out a daub of dark, wet snuff and pack it on the sting site. This poultice lessened the pain and inevitable itch. Such an antidote was readily available in those days, the popularity of snuff being what it was. So we didn't worry about getting stung.

Time changes things, though.

Twenty years ago, my mother telephoned one morning.

“I got bee stung,” she said.

“Where?” I asked, and she knew I meant Where did this happen?

“Up in the ditch behind the house where I was pulling weeds,” she said. “I must've got in a nest of yellow jackets.”

“How many times did you get stung?”

“I don't know.”

I told her I'd be right there. When I arrived at her house eight minutes later, I looked at her arms, neck, and chest, and said, “I'm taking you to the hospital.”

My reaction was influenced by her cousin's recent bee sting—a single one—that landed her in the hospital.

“I'd never had an allergic reaction before,” she'd told my mother and me.

At the emergency room, the attending physician, a large man who resembled Wilford Brimley and wore cowboy boots, concluded that my mother had received thirteen stings. She was given an injection of diphenhydramine and allowed to rest on a bed in a curtain-covered cubicle.

“You were right to bring her in,” the doctor told me. “You never know how somebody might react to a bee sting. A mother's too important to lose.”

Afterward, I took her home with me, where she slept—as the doctor said she might—the rest of the afternoon.

After that day, I began to worry a little more about what might happen after a bee sting. Why I didn't have a strong allergic reaction to my stings in 1964? I don't know any more than why my mother's thirteen stings didn't faze her body very much.

Prior to that August day when my husband ran over the yellow jackets’ nest at our garden, he had experienced a lifetime of bee stings. I witnessed one such time: in the 1980s, he and our collie Laddie trudged into a yellow jackets’ nest on a kudzu-covered bank behind our house. When the yellow jackets started swarming, he and Laddie tumbled off the bank in a tangle of man and dog, Laddie yelping the entire time. But my husband suffered no more than a little discomfort from the fall.

And yet that August evening three years ago changed everything.

Anaphylaxis is a medical term recently added to my vocabulary, a word I'd never heard, a reaction I'd only vaguely feared.

My father, a World War II Merchant Marine, disregarded bees, hornets, or wasps until they imposed upon him. Many times I've seen him clap a pestering wasp between his palms, with no ill effect to his hands, and then wipe the wasp's remains on his pants legs. One summer day when I was a teenager, though, he and I discovered a giant hornet's nest hidden in an apple tree in the side yard. No sooner than we turned to get away from the nest, a hornet dive-bombed into his hand. His hand swelled grotesquely, but he didn't complain. Years before, he had been worried for me, his eight-year-old daughter who was stung by yellow jackets, but he was never concerned for himself.

In those days, none of us worried much about getting stung.

But today, as I work outside pulling weeds from flower beds or, as this morning, spraying my rosebushes, I am vigilant. If I feel the slightest prickly sensation in my pants leg or under my shirt, I run inside and check to see if something has stung me. I even worry about a tiny sweat bee that lights on my arm.

My husband tells me that a new strain of killer bees is making its way through the South. As far as I know, these bees have not yet arrived in western North Carolina.

But I will be watching for them.

Julia Nunnally Duncan is an award-winning poet and fiction writer whose published books include two novels, two short story collections, and two poetry collections. A new poetry collection Barefoot in the Snow is scheduled for a spring 2013 release by World Audience Publishers. Duncan is currently featured in an interview in Southern Literary Review that explores her new poetry book and her life as a poet. She was educated at Warren Wilson College, where she earned a B.A. in English and an M.F.A. in creative writing. She teaches English and Southern Culture at McDowell Technical Community College in Marion, N.C.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: I was surprised at being reminded how many times bee stings had actually impacted my life and that of my family. I found myself more paranoid about being stung, especially during the composition of this essay.