Welcome to Issue No. 67 of Prime Number:

A Journal of Distinctive Poetry & Prose

Letter from the Editor

Dear Readers,

The 2015 Prime Number Awards are NOW OPEN! This year, we're offering prizes in three categories: Short Story, Creative Nonfiction, and Poetry: First Prize--$1,000 plus publication; Second Prize--$250 plus publication; Third Prize: publication. The deadline to enter is March 31, 2015. Go here for information about our terrific judges and full contest guidelines.

Also, we wanted to make sure you knew that Volume 4 from our Editors' Selection series is now available. It includes the first place winners from last year's contest, plus great stories, essays, and poems from our 4th year of publication. Order Editors' Selections Volumes 1, 2, 3 and 4, shipping now from Press 53.

We are currently reading submissions for Issue 67 updates, Issue 71, and beyond. Please visit our Submit page and send us your distinctive poetry and prose. We’re looking for flash fiction and nonfiction up to 750 words, stories and essays up to 5,000 words, poems, book reviews, craft essays, short drama, ideas for interviews, and cover art that reflects the number of a particular issue. If we’ve had to decline your submission, please forgive us and try again!

Readers sometimes ask how they might comment on the work they read in the magazine. We’ll look into adding that feature in the future. In the meantime if you are moved to comment I would encourage you to send us an email (editors@primenumbermagazine.com) and we’ll pass your thoughts along to the contributors. Similarly, if you are a publisher and would like to send us ARCs for us to consider for reviews, please contact us at the above email address. We’re especially interested in reviewing new, recent, or overlooked books from small presses.

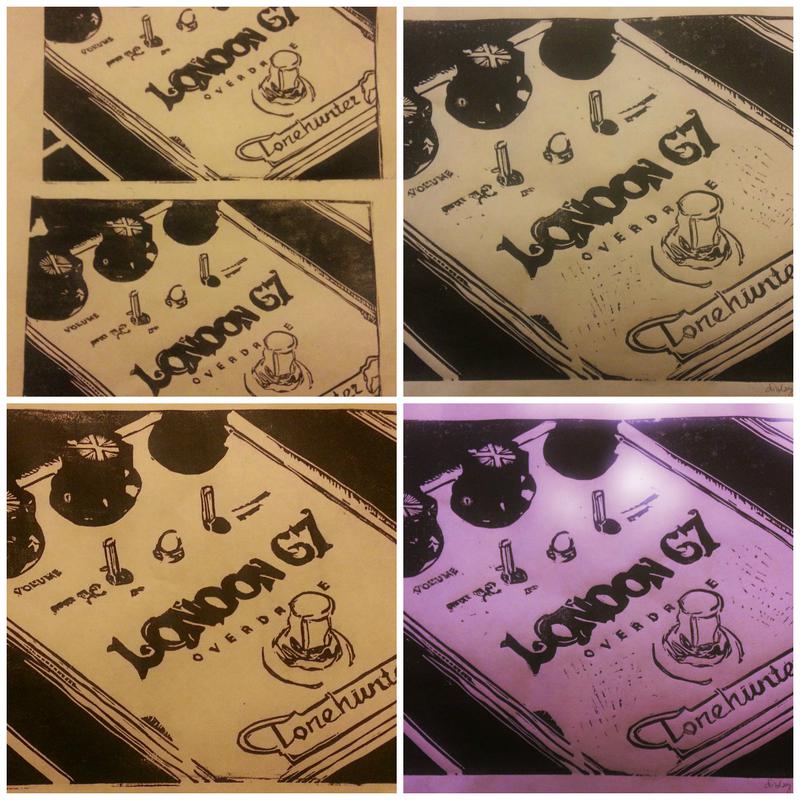

See our cover image above? That's a print made from a handcut linoleum block by Lindsay Curren. We asked Lindsay to describe the process of making this print, and you can read all about that here.

One more thing: Prime Number Magazine is published by Press 53, a terrific small press helping to keep literature alive. Please support independent presses and bookstores.

Clifford Garstang

Editor

Issue 67, January-March 2015

FICTION

Grief Showers

Second Run

POETRY

Regarding the Dead Lobster Found at 60th and Stark Street

Saying Adieu to the Season of Exploding Hearts

Sap

Response to: Step on a Crack

Response to: Don't Swallow Your Gum or it Will Grow into a Tree

Response to: I Don't Believe You

Response to: You're Going to Dig a Hole to China

CREATIVE NONFICTION

The Blind Seer

The Secret Places

INTERVIEW

Interview with Sergio Troncoso

REVIEWS

Review of The Blessings by Elise Juska

Review of Escape by Dominique Manotti

Review of The Cartographer's Ink by Okla Elliott

Review of The Poison that Purifies You by Elizabeth Kadetsky

COVER ART

Grief Showers by Nick Ostdick

Followed by Q&A

Quinn yanks back the shower curtain and says, This isn’t about sex, scanning my body in suspicion. She’s naked and startling with her milky blue eyes. Her tuft of blond hair is tangled and slick. Her body is still recovering, the skin around her stomach and hips a fat pudding. Good, I tell her, the shower still cool. Then it feels like an entire year goes by, every season in silence, and I wonder how long we’re going to be like this—if anything will ever feel like it did before. There was a time when just a glimpse of her bare, shiny shoulders would make me want her in this desperate, end-of-the-world-fuck-each-other-to-death kind of way. Apocalyptic love. But now when she steps inside the water spurts and chokes and goes icy cold because the pipes in the apartment are terrible and fledgling and the old woman upstairs lets her faucet drip and drip 24/7, and I flinch and curl to hide my parts like a secret is scribbled in bright black ink across my stomach as Quinn brushes by me and says, What’s the problem? I tell her the water is too damn cold and she nods once like she isn‘t buying it but like she also doesn’t really give a shit, and I swear: the end times could come crashing through the bathroom window, the stars burning up and the moon melting into the sea and the waves swallowing up the shore, and we probably would just look at each other and shrug and wonder what all the noise is about.

I’m running late, Quinn says. It’s just a convenience thing. What, do you mind?

No. I crack my knuckles. Not really.

It’s Quinn’s first day back at work. She’s taken some time off her gig as a receptionist at the gum factory in Cicero. It was only supposed to be a few days but it’s turned into damn near three weeks by now and I miss the way she used to smell of spearmint, how she’d fill the apartment with her minty flavor. I work there too on the loading dock, which is how we met, one afternoon when she came looking for one of my boys with a phone message from this girl he was seeing. Man, you should’ve seen Quinn cross the dock, real graceful and smooth like a movie girl on camera with a click of her shoes and that slim, bendy figure, and when she asked me if Tommy was around, the note feathered between her fingers, I looked her up and down and said, Tommy ain’t gonna appreciate anything you give him.

Honey-tongue, she said, and then boom, it seemed like we were living together in a matter of seconds.

That note: Tommy’s girl was pregnant. She called reception. She left a message. Quinn took it down—With child, yours, for real.

Quinn said, I didn’t want to tell you like that, sandwiching my left hand between hers one night on our sofa not long after she moved the last of her stuff in, empty boxes stacked near the back door. She was smiling. Red orbs for cheeks. And then she wasn’t. Wasn’t smiling. Wasn’t pregnant. Wasn’t orby or colorful. Just like that. Just a few months in and everything went haywire inside her. I told her it’s like running the ball up to the ten yard line and then not being able to get it across.

What does that even mean? Quinn asked from the far side of the kitchen table, knees up, shaking her head. She was half down a bottle of gin a night or two after we lost the baby. Windows open, sky perfectly dark, like the stars skipped town. She was wearing my sweatshirt and nothing else and the lone bulb above blinked and dropped shadows onto her the slope of her nose. This was our daughter, she said, Not some dumbass football game. Jesus.

I think this might be where the trouble started, because even though she was pissed at me about the football thing, I think she was terrified of being alone now. Like she had gotten used to always having something—or someone— so close. When I’m in the house, she can’t let me alone. When I’m dropping a deuce, she leans against the closed door and talks about a Judge Judy marathon she’d watched that day: And then the mom was screaming at the daughter and the daughter was screaming at the mom and it was great. She calls me at work and when I answer she says, It’s me, and I say, And? and she replies That’s all, and I tell her goodbye and she says, No, not yet, and makes me stand there listening to her breathe heavy and muffled as if the receiver is tucked inside her mouth.

When I get home and dinner still isn’t ready yet, she asks me how my day was and before I can answer she’s off to the races gabbing on and on without letting me have a turn and nothing short of telling her I’m going to knock her to the moon can stop her. Or she hops into the shower with me, like right now, just slips right in while my face is sudsy and my eyes are shut, and either just stands there and watches or maybe Nairs the tiny freckles of hair beneath her nose.

She angles some water into the crook of her armpit. The piney smell of an unwashed body fills the air. She doesn’t say much, not anymore. It’s like losing the kid had broken her tongue, and she doesn’t even look like my wife anymore—her underarms are doughy and rippled and can swing like a hammock and she has sallow cheeks and gnarled fingernails. She looks like an impostor. A dime store Quinn. But I guess that’s the thing when you lose a child: everyone looks poor and fake and remarkably unfamiliar.

But the worst part, the absolute worst thing of all, is those stretch marks. Those pinkish-brown lines etched from her bellybutton down to her hips. They still haven’t cleared. Fact is, it looks like they’re getting darker, more pronounced. Is that even possible? How much worse can it get? I want to ask her and like she can tell, Quinn rinses herself thoroughly, one side of her body and then the other, and then squirts some watermelon smelling shampoo onto a washcloth and works the white foam over those marks, back and forth. She goes up and down. She scrubs hard. A housewife trying to pull a stubborn bourbon stain from the good carpet.

Then she stops. She pinches the washcloth between two fingers like how we were told to hold a dirty diaper. She lifts her head to the ceiling, to the watery shine of light coming down. Her neck is all lines and veins and she says, If you don’t stop looking at ‘em, I’m going to pull your fucking eyes out, her voice so soft and low that for a moment it doesn’t even register.

What are you talking about?

She tilts her gaze at me. Stop it. You’re always staring at them and it makes me feel like shit.

Quinn blows a breath through her nose in frustration and goes back to considering the ceiling, eyes closed. And here’s the thing: I’d be more upset or freaked out that she just made plans to remove my eyes from my head had she not caught me. Had she not been right. Busted cold. Red-handed thief. I know I stare at those stretch marks, at her flabby, there-used-to-be-something here stomach. Even through her t-shirts, especially through those papery blouses she wears that kind of flow and drip over her shape. I try not to but it’s no use. Tractor beams for my eyes, drawing me in, and I hate them. Reminders, you know? Like some fucking sick memorial of what we got so close to before ending up so very far from. They’re gross. I make a face, scrunch my neck. She must loathe this face as much as I loathe the very middle of her body.

Tell me, Quinn says, her teeth so close to my lips, my cheeks. Tell me why.

There’s nothing to tell. I love you. We’ll be fine. It’s just a rough patch. This is normal. We’re tough. Your body is like a fucking amusement park and all I want to do is go for ride after ride.

Put these under things I should say, things a good, decent husband would offer. But instead I jam my face beneath the shower head and let it wash through my hair and down my shoulders and say, I don’t know, but I can’t stand them and if I had X-ray vision, I would glare at you until they burned right off.

You’re so selfish, Quinn says, shoving the washcloth to the floor.

Right, ‘cause I’m the one who calls you constantly at work and won’t let you shit by yourself.

Her eyes thin to tiny slits and her chest heaves. I can hear the rush through the walls now and the knocking of pipes above and then the water temp spikes and we both hug opposite sides of the shower, careful not to touch the stream, errant spray finding our foreheads and toes. When it finally cools down and we step back in and come together, Quinn looks concerned and thoughtful. Her mouth is small and smart. She glances up at where the plumbing is still creaking.

X-ray vision, huh? she says.

I don’t know what that meant, I reply. Craziness, I guess.

Let’s try it, and she drops into a crouch over the drain, a leg on either side, and once she steadies herself she braces her hands flat behind her with her stomach sticking right in the torrent. She blurts a fat, drunk laugh, wobbling a little until she finds her center. She looks like a child crabwalking in the rain, hair pressed flat and mouth hanging open in excitement. She looks like she’s about to make right in front of me, but instead she jabs me with her knee and says, Make it hotter, Danny. Let’s do it. Let’s burn ‘em off.

Huh?

Yeah, yeah, do it for me, her eyes lit and full. You know you want to, she whispers. You know you do.

Aches in my ribs. Pangs in my throat. My heart going off like a whole band of bass drums in my head. I watch her wait for it, the pain, the searing. I finger the dial. She winces. Steam gathers and grows and she cries and her entire body shakes like it’s coming apart from the inside and I keep on the dial, even after she stops asking me, the hairs wilting off my ankles.

Later on we’re in bed. Quinn doesn’t go back to work today. How can she? Her entire body is appled and sore and all she can do is lay on her back while outside the sky pinks up and then darkens. Of course it didn’t work and she says, That wasn’t really the point, was it? and because she says it like that, like a question, I feel guilty and mean. The words sound like blame. Her voice pitches it that way, like this is something I’m going to pay for. Don’t worry, she says after a while, moonlight fanning across our sheets. It was a grief shower. We’re weren’t thinking clearly. I feel her try to move now, stiff Frankenstein lurches as she reaches over and tickles a hand into my underwear and grabs my dick and starts stroking it. Halting. Awkward, but not entirely bad. This’ll make it better, she whispers into my ear. Pretend the world is ending. Pretend it’s almost over. C’mon, she adds, It’s nearly done.

I close my eyes. I breathe long. I let her keep going and whisper it sure feels like it.

Nick Ostdick is a husband, runner, writer, and craft beer geek who lives and works in West-Central Illinois. He holds an MFA in creative writing from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale and is the editor of the hair metal-inspired anthology, Hair Lit, Vol. 1 (Orange Alert Press, 2013). He’s the winner of the Viola Wendt Award for fiction, a Pushcart Prize nominee, and his work has appeared or is forthcoming in Exit 7, Annalemma, Big Lucks Quarterly, The Emerson Review, Midwestern Gothic, Fiction Writers Review, and elsewhere.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: The ending, both in the original draft and subsequent revisions, really crept up on me and still surprises me even now, in part due to the rawness of it but also because that’s really where the story and characters took over and left me behind. Attempts were made in alternate versions to confine everything to the shower stall, however, these two characters kept resisting that containment from the get-go.

Q: What’s the best writing advice you’ve received? Did you follow it? Why, or why not?

A: I’ve been fortunate enough to study with, learn from, and buddy-up to a number of super-talented writers, which means I’ve been on the receiving end of so much wonderful advice it’s hard to zero-in on one particular dictum or mantra or code. But the one thread that sticks out amongst all the nuggets of wisdom is time and trust: in other words, writing is hard and you have to give yourself time to let the story unfold and trust that it’ll find its way. Of course, you have to work at it, but you also have to let the characters and scenes and ideas marinate and mingle. I think that’s a tough thing for a lot of writers.

Q: What three to five authors and/or books have inspired your journey as a writer?

A: Stuart Dybek’s The Coast of Chicago – J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories – Richard Ford’s Rock Springs – Junot Diaz’s Drown – and Lorrie Moore’s Self-Help. Phenomenal collections all.

Q: Describe your writing space for us. Are you someone who finds the muse in a public space such as a café, or in a cave of one’s own?

A: My ideal writing space is the one that’s working for me right now. In other words, some days it’s at the desk in the spare bedroom of my home, others it’s the back table near the men’s room at my local coffee shop, or at my desk during lunch.

Second Run by Michael Overa

Followed by Q&A

“They see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another,

which the fire throws on the opposite wall…”

-Plato, Allegory of the Cave

The empty lot used to be a supermarket until it was torn down. Weeds and dying grass stitch together the broken concrete. Cans, cigarette butts, and crumpled fast food wrappers drift across the asphalt. Laura ducks through the gap in the chain link fence at the far end of the lot, where the metal has been peeled away from the posts. The reader board above the Valley Movie Theater is a dingy yellow wedge pointed at the highway. The mismatched letters are a collection of black and red, numbers stand in for both capital and lower case letters.

Laura pulls her baggy jacket around her as she enters the stale popcorn smell of the lobby. The intermittent sounds of the video games lined up along the far wall bang and rattle. She ignores the vaulted ceilings and stares the duct-tape patched carpeting.

In the small break room Laura takes off her jacket and puts on the red bow tie and satiny black vest she’s required to wear. The daily assignments are listed on a clipboard hanging from the wall. She stares at the list and tries to focus on the names. This is her seventh shift in as many days, and she has had a hard time sleeping, the evening shifts throwing her schedule out of whack. Laura’s daily assignment, along with Chance, is: “Guest Comfort”.

She pushes through the heavy metal door and emerges into the lobby. Manager Dave and Crystal are behind the concession’s counter. Dave is explaining something about the soda machine. He dumps pitchers of ice into the top of the machine and checks the syrup levels. Crystal is newish, a high school kid. Laura has yet to have a conversation with her, but they’ve been introduced several times.

When a movie lets out Laura and Chance stands in the hallway making sure no one screen surfs from one movie to another. A movie is letting out, and several families make their way towards the lobby – small kids sprint down the hallway. Smaller kids are carried by their parents. Here in the lobby the lighting prevents shadows. During the summer, it isn’t until you exit the building that the sun stings your eyes; the overwhelming brightness.

Laura and Chance stand aside and let the families pass. When the next film begins they stand at the entrance to the long hallway and collect tickets, dropping them one at a time into the podium situated between scarlet ropes. Once the film starts they walk through the theater and to make sure people are reasonably well behaved. After the movies end they walk through the cavernous screening rooms and pick up Abba-Zabba and Butterfinger wrappers. They sweep stray popcorn from the sticky floors.

Rain scatters against the front windows. It promises to be a slow night, which is good. Laura will be able to slip into one of the movies and watch, or, more likely, fall asleep curled in one of the chairs in the back row. She never has much trouble sleeping here. There is comfort sleeping in a large room as a movie plays. The soundtracks and dialogue invade her dreams.

A young couple comes in and heads into a movie that has already started. They’re ten minutes late, but they don’t seem to be in a hurry. They are high school kids, probably seniors. Crystal nods to them and smiles in a way that says she knows them – a dim familiarity. Chance walks over to where Laura is running the vacuum back and forth over the same patch of carpet.

“We could mess with them,” he says.

“We could,” she says.

Chance shrugs and walks away. Laura vacuums the threadbare carpet. When she is done with one patch she puts the vacuum away and checks the ladies’ room. She scoops a handful of crumpled paper towels off the counter and tosses them in the garbage. The arcade games along the wall make roaring spaceship noises and the sounds of explosions and gunfire.

The rain is comes down in sheets, creating broad lakes of water in the low areas of the parking lot. A group of teenagers comes in. Four in all, moving like puppies, clumping together, tripping over one another. They yap and bark at each other. They shake their coats and throw back their hoods – the shoulders of their jackets stained dark with rain, and hair dripping across their foreheads. They split into groups, the girls head to the concessions counter and the boys head towards the video games. Chance straightens up and walks around the concessions counter to help Crystal with the orders of popcorn, extra-large sodas, Jujubes, Junior Mints.

Laura positions herself behind the podium between the ropes. On the top are numbered slots – each slot represents a screen. The kids bound up with popcorn and sodas and candy.

“Screen Four, down the hall on the left,” she says tearing the tickets.

“Screen Four,” she says, “Screen Four.”

She hands the tickets back and drops the stubs into the slot for Screen Four. Chance heads back to start the movie, and Laura goes past the other screen to check on the couple in Screen Two, whose movie will be ending soon. The couple is sitting in the middle row in the middle of the theater. The girl’s head leans on the guy’s shoulder and his head is leans over on top of hers. The way people stare straight forward at the screen for hours at a time is always strange to her.

Laura watches the screen a moment before slipping out and down Screen Four. The kids have the theater to themselves. They jump over the seats and throw popcorn at each other. The two boys are up near the projector window creating shadow puppets on the screen. Laura is beyond caring whether or not they mess up the theater. In the hallway she runs into Chance. He asks if the kids in Screen Four are behaving.

“Like kids,” she says.

“Did you talk to them?”

Laura shrugs. The wind buffets against the lobby windows. She stands staring at the windows. David asks if she’s already checked the bathrooms.

“Take your fifteen,” he says, “send Chance when you get back.”

Laura grabs an extra-large soda from concessions, hoping the caffeine will keep her awake. The syrup coats her teeth in sugary fuzz as she sits otherwise motionless at the break table. The sugar sits like a ball in the pit of her stomach. She feels tired and slightly sick from the soda. She walks through the lobby and nods to Chance and Chance nods back and heads to the break room for his fifteen. In Screen Four the kids have mostly settled down and are intermittently shouting at the screen.

She continues to vacuum, not because the carpet is dirty, but because she has nothing else to do. She vacuums down the hall, edging in overlapping angles. One of the boys from theater four comes out, full of a smiling, predatory energy. His age is hard to discern. He watches Laura like he has the perfect joke. Laura looks up at him as he pulls a crumpled pack of Marlboros from his jacket pocket.

“Smoke?”

“I just took a break.”

“You look busy.”

Laura glances up as Chance comes out of the break room. He slips his cell phone into his pocket and walks over to where Crystal is leaning on the counter, no doubt leaving greasy arm prints on the glass. She figures that David much be in the office. Laura slips into the break room for her jacket and walks outside with the boy.

In the alley behind the theater, near the dumpsters, he puts his back to the wind and lights his cigarette, then shields the flame for her. She has to lean close-ish to him, and she can see the black crescents of his fingernails as the flame wavers. They stand exposed to the wind and rain, trying to use the dumpster as a windbreak. Smoke drifts up and away from them in stages – blowing first one way and then another – sometimes just hanging low beside them like some sea creature caught in the wavering undercurrents of the wind. Shadows of trees waver on the wall above and behind them. He drops his cigarette and chases it with his foot, dragging a toe across the cigarette as it rolls away. Sparks scatter into momentary constellations.

Laura shivers and takes a long last draw on her cigarette. The kid skips and hops next to her as they enter through the front door of the theater. Chance looks up at her curiously and Crystal smiles with a knowingly. Crystal’s smile is the secretive sort that seems beyond her high school years. Laura hangs up her jacket in the break room; the cold dampness of the jacket in her hands.

She refills her soda, the straw squeaking as she stabs it through the lid. The taste of wax and sugar and cloying syrup. It’s barely keeping her awake. The young couple that was alone in screen two walks out arm in arm, and Chance walks down the hall to clean the theater. Even though there were only two people in Screen Two Chance will walk down both aisles and check most of the seats, sweep the floor. For the most part it is another way to take up time; to inch ever closer to the end of the shift.

Shortly after the couple leaves Dave sends Chance home. Chance jogs across the parking lot to his car. Laura watches as the headlights come on, and the wipers bounce across the windshield. A low cloud of exhaust builds turning red in the brake lights before Chance tears across the parking lot and out onto the highway.

There is only one more late night showing, the 12:10. And the three of them: Dave, Crystal, and Laura will be enough to close up. They’ll shut down Screens Three, Four, and Five and it will be even easier to close. They have to stay through the first half of the film before they can shut down if no one comes in.

Screen Four lets out. The kids come out into the hallway, slightly more subdued then when they went in. Two of the girls are walking arm in arm, weaving against each other. It’s obvious that they’ve been drinking. It’s not unusual. In fact, it’s such a common thing; they almost assume that it’s going to happen.

Passing into the lobby The Kid stays behind. He digs into his pocket and pulls out a handful of quarters. Standing before the shooting game, feet at shoulder width, he begins pumping quarters in. He takes it seriously, eyes locked on the screen. There is intensity to the way that he shoots. Focused and determined. He lines up quarters on the ledge of the game so that he can pump them in one after another. When he runs low he jogs over to concessions and cashes in several crumpled dollars for quarters.

Dave comes back down the hallway having locked up all the screens except Screen One. The film is cued up and the cinema is reasonably clean. Dave sends Laura to gather up the garbage. She takes the rolling trash bin from the cleaning closet and pushes it down the long hallway to Screen Five. After emptying the trashcans beside the entrance to each screen Laura trundles the cart outside. She shivers as she heaves the cart over the ruts and cracks of the uneven parking lot.

Laura realizes that what she thought was rain is only water flying off of the trees in the parking lot. Bright colored leaves plaster themselves to the cement – bright oranges, yellows, rust reds. The colors only slightly muted by the damp. As she parks the gray bin at an angle next to the dumpster to keep it from rolling away she wishes she’d grabbed her jacket. The lights on the side of the building are a dim fluorescent glow. She hoists one bag onto the lip of the dumpster and nudges it. She listens to the heavy thudding of the bags as they hit the bottom. The hollow bass sound as echoes down the alley.

Cigarette butts cluster at the base of the dumpster. As she lets the dumpster lid drop back into place Laura wonders how old The Kid actually is. Above her, on the wall, the shadows are painted on the bricks. She wheels the bin back towards the front doors and through the lobby, but The Kid is gone.

There’s a slow dissipation of minutes as they wait for the evening to end. Dave, Crystal and Laura lounge at the concessions counter, watching the clock, hoping that no one else will come in so that they can leave early. Laura thinks only of curling into her bed and cocooning herself in the blankets and pillows. Dave and Crystal are talking about new movies that they wish were playing at the theater. Dave has an encyclopedic knowledge of films.

“I wanted to be a director when I was a kid,” he says.

“I think it would be cool to be in a movie,” Crystal says.

“Sure, acting is one thing,” he says, “but directing.”

“If the movie flops it’s always the actors.”

“The audience only sees what the director wants.”

Laura refills her soda yet again and replaces the lid. Dave checks his watch and says they might as well shut it down. He locks the front doors and turns off the sign. He pulls the tills from the ticket booth and Laura and Crystal set to work shutting down the concessions counter, wiping down the surfaces and restocking the candy. The cinema is quiet and chilly. At a quarter to one they are turning out the lights and gathering at the front door, while Dave sets the alarm and then lets them out into the parking lot. The rain shatters the smooth surface of the puddles. Crystal climbs into her boyfriend’s pickup and Dave crosses to his sedan. They shout goodbyes to each other.

Laura walks around the end of the building and ducks under the fence and pulls her jacket tight around her. The heavy wind pushes against her thighs as it comes low across the parking lot, rattling empty wrappers and beer cans. She reaches the far end of the parking lot and glances over her shoulder at the empty lot. Inside her apartment she locks the door and crosses to the window and looks down at the street. In the early morning breeze there is nothing but shadows.

A Pacific Northwest Native, Michael Overa has worked with 826 Seattle, The Tinker Mountain Online Writers’ Workshop, the Richard Hugo House, and Seattle’s Writers-in-the-Schools Program. Michael earned his MFA in Creative Writing from Hollins University in Virginia, where he was a 2009-2010 Teaching Fellow. During the 2013-2014 academic year Michael also participated in the Teaching Artist Training Lab at the Seattle Repertory Theater. His work has appeared in the Portland Review, Fiction Daily, Husk and Syntax, among others.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: Although it wasn’t initially part of the drafting process I went back and re-read Plato’s Allegory of the Cave during early revision. Initially I was worried that the connection between a movie theater and the allegory would seem cliché. Then my concern swung the opposite direction. Ultimately I decided that the epigraph was necessary as a way to frame the story.

Q: What’s the best writing advice you’ve received? Did you follow it? Why, or why not?

A: I think most of us have received an overwhelming amount of advice over the years, (most of which we don’t follow). The one piece of writing advice that I try and follow diligently is Hemingway’s idea that to be a writer one must go away and write.

Q: What three to five authors and/or books have inspired your journey as a writer?

A: Like many other young writers one of my earliest influences was Hemingway. Nowadays I go back to Don Delillo’s Body Artist once or twice a year. I have recently gotten into the short stories of Richard Bausch and Karen Russell.

Q: Describe your writing space for us. Are you someone who finds the muse in a public space such as a café, or in a cave of one’s own?

A: At the risk of sounding like the stereotypical Seattle writer, I do most of my writing in coffee shops, which have become my defacto office. I’m prone to hunker down in a corner with my unlined notebook and pen for first drafts – for later drafts I drag along my computer.

3 Poems

by Mimi Herman

Followed by Q&A

On a Scale from Yes to No

Fall falls off the map,

a cliff at the far right edge,

the east at 3:00 am,

where light refuses to penetrate.

We are all getting older

but not at the same rate.

I watch my father shrink into himself.

The circles of his acquaintance

Narrow in circumference.

The lenses of our eyes harden

until we can’t see what is closest to us

unless we hold it at a distance.

Nouns evade us.

Our fat, stiff, trembling fingers betray us.

We say no more often.

In the east, off the map,

the sky gains color by degrees.

The light hardens

until we can’t see what comes after us in the distance.

Hold it close.

There is a sea

where everything we might have done drifts

amid thick stalks of kelp, rooted and swaying,

small fish darting in the dark,

swift against the slow ache

of larger tides.

Max

For Max Steele

Early this month you began popping up from the dead,

With your It’s all about me smile,

That made you, at eighty, the rock star

Of the Whole Foods breakfast crowd.

I wondered why you were so insistent

About interrupting the month of August

Until I recalled that we were striding toward

The anniversary of your death,

The way you insisted we pretend to stride

Toward the camera, in the photograph

That sits on my desk, because

Movement makes a picture more interesting.

I went to visit you in the hospital,

Not to pay my last respects,

But with the intention

Of embarrassing you back to life.

You’d be so angry at me for seeing you—

Breathing tube, IV drip, backless gown—

That you’d have to come back

To tell me how rude I’d been.

You were the one who told me about the wonderful word

That inhabits half the parts of speech—

Exclamation, adjective, noun, verb—

As in the sentence, which pretty much describes

The way I feel today,

When you, four years dead and still insistent.

Inhabit half my waking thoughts:

Fuck, the fucking fuckers fucked it.

You were the one who told me

How halves multiply on a page

So if you write about one half of anything,

Sooner or later another half of something

Will have to come and join it, and another

Until you have a whole

Cocktail party of halves,

Catching up on all they missed while they were apart.

Yes for These Few Hours

In the barn, spare bedrooms, and all around the bonfire ashes,

guests from your friend’s party

are snoring off the half-lives of good beer and cheap wine.

The kitchen counters by the open door

are lined with half-filled mugs and glasses

where intoxicated insects have drowned.

It’s been hours since our host

climbed the stairs with his patient wife.

Wrapped in scavenged afghans, we occupy the couch

a rowboat in a sea of mess.

All has been yes for these few hours

in the middle of years of no or probably not or I just don’t know.

We’ve had two decades together apart—

apart, together. Every year I see you

on my continent in this one place.

Then you fly home to ring me up,

after closing time, drunk enough

to say come hither from three thousand miles away.

We’ve invented a language where we substitute other people’s names

for the things we can’t say about ourselves.

When you describe your friend’s colon cancer, you mean

things get twisted up inside you.

Now say morning won’t come.

I won’t have to look in clear light

at what we’ve done. The night

is drifting from your mouth to my hands, while outside

someone fries up bacon on a griddle.

Hangovers moan, cramped from awkward sleeping.

I only wanted a little more time, so I would know

that you would stay if I didn’t let you go.

Mimi Herman is the author of Logophilia and The Art of Learning. Her writing has appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Shenandoah, Crab Orchard Review, The Hollins Critic and other journals. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Warren Wilson College, and has been a writer-in-residence at the Hermitage Artist Retreat and the Vermont Studio Center. Since 1990, she has engaged over 25,000 students and teachers in writing workshops. With John Yewell, Mimi offers Writeaways retreats for writers in France and Italy, and on the North Carolina coast. You can find her at www.mimiherman.com and at www.writeaways.com.

Q&A

Q: Memory holds us together, keeps us apart in these poems. What is your earliest memory?

A: My earliest memory is sitting on the porch with my friend Luther, who took care of the old lady who lived next door. I’m guessing he was about 45 and I was about four. Aside from Pup-dog and my (female) pony, Jim, Luther was my best friend.

Q: Paper or screen? Pen or pencil or stylus?

A: Paper (white legal pads) for poetry, with lots of crossings-out and scribblings-in. I’ve finally weaned myself from paper to screen for writing novels—but it was a long and arduous process. Definitely pen—a fine Uni-Ball in black. I buy them by the dozen.

Q: Can you tell us a bit more about Max Steele?

A: Max was one of the great mentors in my life, who shaped me as a writer and probably as a person, too. I spent many hours in my junior and senior years at UNC-CH curled up in his office armchair, as he dispensed wisdom with the air of someone who is certain he is the wisest person in the room—which he generally was. Max was the consummate flirt, not for romantic gain, but to charm others by putting them on edge and at ease at the same time. I learned from him that characters in stories had to have jobs and pay rent. They couldn’t just live in some limbo-land. And I learned from him how to throw a perfect party: invite interesting people who have nothing in common and serve them foods that only you can procure. When I graduated from Carolina, Max stunned me by throwing a party for my family and friends. I still can’t think of him without wanting him back.

Q: Write one half, and another will come to join it – can you talk about how this works in your poems?

A: Literally, halves replicate on the page—though whether this is the power of suggestions or something deeper, I don’t know. I’ve never written the word “half” without another “half” appearing within a page or two of it. Metaphorically? I don’t know. I’m so charmed by the literal reproduction of halves, I’ve got half a mind not to go any further with it.

3 Poems by Judith Pulman

Followed by Q&A

Regarding the Dead Lobster Found at 60th and Stark Street

I don't know why it's there either.

His thick shell has turned maroon.

Flies circle the fetid patch of pavement.His feelers

Fell limp, green, down. He makes me think

Of you. I'd like to laugh it off

As some schoolboy's gag. Instead, I recall

The last time we spoke, when your eyes bulged with

Shock and your back clung to the barroom wall.

I would never leave a lobster thus,

Restlessly pinching into the damp

Air that never offers breath. People rush by

And don’t catch his choked gasps, or the cramp

Before his final grasp. Why couldn’t you speak,

That night all walkways turned to mud

And my fingers spun the air into punctilious maps?

I tried to prove our paths should split. That it was silly,

Us together. A reckless choice. A judgment lapse.

Did you put this lobster here, in front

Of my apartment? Once, I thought myself guileless.

But this lobster curdles my blood, his blunt

Claws slightly open, like your lips then, lunging

To express any spare oath between us, only

To choke on barnacled facts. Your cheeks

Turned blue, as if resigned to breathe

No more. I watched you retract

Into your crimson shell. What could I do but leave?

I hate this lobster. Not that I blame

Myself for his rancid presence or tragic end;

But who would pull him from the tank, claim

This creature, and drop him to rot, to fend

For himself on this rough ground. Be glad,

Dear, that you’re not dead, just without

My embrace. I didn’t know you loved me—

Would it be different if I had? I don’t know

And I’m sorry. Dear lobster, grant me grace.

Saying Adieu to the Season of Exploding Hearts

The season of exploding hearts ended with a bang.

Our newscasters blame hard water. At Hunan Delight they say

that last year was a tiger year, most of us just pray

the cause of death won’t correlate with our current pangs.

Still, the public sector’s burgeoned: our kingdom’s bounds

have grown with the graveyards. No—no: there is no sound

or sane way to mourn so many, to be so without.

Religion makes our mouths dry up, as does the local gin,

and when we kiss each other, we don’t feel a thing

except for our eyes closing, except ourselves being blotted out.

Why did their hearts burst and why didn’t ours?

There is no way, the doctor said, to clean out certain clots,

so we accept our certain today and give the past to the dead.

Not dying takes a lot of luck, we say to our spouses

and we know we’ve said too much again, as their faces

quiver at the thought of our blood gone blue and our head

sans pillow dropped back in an icy box.

We’re hurt, we don’t mean it, we just talk

as if we were the town puppeteer who daily played

on a cardboard stage and there wept and there could dream—

we aren’t that. With no formal goodbye,

all we have is our quiet collective scream.

Sap

You are walking me home through the rain

And I don’t want to start up on death again,

But what else is there? You point—“That’s dogwood,”

You say. Not a man of many words,

You lay a bud behind my ear.

Our hands brush up. You’re a bit near,

Don’t you think? The rhododendron

Is flourishing, you say it’s among

The vibrant evergreens, it doesn’t go

Away. I don’t know it; my dear fellow—

Blooms are for graves, not me. You’ve barked

Up the wrong bush. Shrub. Whatever. It’s dark

But your eyes shine like emeralds.

You hand me a broken daffodil, a herald

To lame beauty—I don’t want it. Still you smile

Like a predator; without my wit or guile,

I keep mum as you invoke the azalea.

Why are you staring at me? I impale a

Red petal with a knobby stick.

I’m not for loving either, made just to pick

Up branches and find a place to hide

Them. How did we get here? We both ride

On the porch swing, shifting lightly.

It’s a dread moment—softly, slightly

You reach for my limb—my wrist—

And I watch. I guess stately redwoods twist

About themselves to bear sticky-sweet juice—

So you say—or I think—squeezed loose

Of the dead roots, I reach for you too

And bury myself in these few

Moments so much greater than sympathy—

Without naming a thing, except for the trees.

Judith Pulman earned her MFA from the Rainier Writing Workshop at Pacific Lutheran University and an undergraduate degree from the University of Virginia. She writes poems, short stories, and personal essays. She also translates Russian poetry, just to keep things light. She has publications in or forthcoming from The Writer's Chronicle, Brevity, Los Angeles Review, New Ohio Review, Basalt, Under the Gum Tree, and other journals. She works as a teacher, administrator, and freelance editor.

Q&A

Q: Memory brings together the oddest things – a former lover, a lobster in the street. What is your earliest memory?

A: Growling at my father when he woke me up in the morning. I had a very pronounced speech impediment until I was 12 or so, and I would express myself with noises rather than using words that I would inevitably mispronounce.

Q: Paper or screen? Pen or pencil or stylus?

A: Pen on paper for drafts and a glowing screen for revision. I am a methodical creature except when I am hungry.

Q: There is a language of flowers, of course – would you talk about the naming of trees?

A: “Sap” is a poem that follows a traditional elegiac theme: turning away from the deceased and back out into the wider world. The naming of the trees gives the speaker something new to fixate on, separate from the losses she has experienced.

Q: Given the strong presence of nature in these poems, winding as it does into the human-carved landscape - do you have a favorite nature poet, who and why?

A: I don’t know if Linda Gregerson is ever referred to as a nature poet, but she writes beautiful poems. I appreciate the unsentimental way that she writes about humankind’s uncomfortable relationship with the natural world. I was brought up in the suburbs of DC and now live in Oregon; I knew nothing about the value of composting until I was 27. It takes a long time for people raised with a suburban or urban ethos (certainly did for me) to grok the idea that we are living in a closed system and that no action or object in the world just disappears. So I enjoy nature poets who take me on the journey from the cities where I actually live out into nature.

3 Poems by Steven D. Schroeder

Followed by Q&A

The Book

The cover was all wrong.

The strongman killed his brother

for it, his brother who purged

all entries from circus to city

for refusing an order to fire

on civilian, also murdered.

Official versions overwrote

every nigger with happy puppy,

and we ripped out every cigarette

as rolling paper. When the map

chapter proved subversive,

the border burned. The first page

covered for what passed

as civil government to pass

laws that prevented passing

security checkpoints. A hollow

in the inner margin was just

big enough to smuggle one bullet.

We couldn’t call it the gutter.

We couldn’t pull the trigger

off the shelf. Who sold out

that we stole the letters

needed to cover each other

with good luck, motherfucker

for good luck? For God’s sake

and ours, they said, they locked it

in a glass case and cracked

our glasses. Our names went in,

no word came back. To break

our spines, mandatory sentences

lined us up and lined us through

and didn’t end when we read

the end. In indices, we found

friends and lovers who signified

the vanished, fugitive and dead.

Oh what a shock to look up

over on a body only to discover

the cover shut on us.

Henry Repeater

Henry Repeater, he introduced himself

twice to the chest. We dubbed him

Double Barrel since we didn’t know shit

from shotgun, antler from greenhorn.

Dime novels claimed his mama

gave him the Christian name

Samuel and the common name Sammy

Smile, but he gave them away

to wander a badlands panorama.

Once, the stranger formed a posse

of just a pistol and a glass eye

painted with a noose. His good eye

did evil in Deadwood years before

he blew through the prairie

and the saloon doors on a stormcloud.

Our guidebooks highlighted

favorite bordellos and outhouses

with bullet holes. They translated

every use of bullseye and cowpoke.

We called him Wild Hoss, branded

by his keepers, who kept our hands

inside the tram windows to keep them

from coming back stumps.

Arrowheads shafted through their hats

always aimed at the gift shop.

While the man saddled an appaloosa,

they showed how to mix whiskey

with wishes in a spittoon,

making wickedness. When he tried

to ride into history, they rustled

one lucky winner a carousel pony

and a scope contraption with a trigger

A for Ask him to come back

or trigger B for Bushwhack.

Both at the same time at ten paces

waylaid our antihero facedown

in the mud, opened his coffin

and made him cough up his true name,

too soft and bloodstained

to understand.

Questions?

What catastrophe? Who disastered?

When did past go? How far underground

did escape tunnel? Where did we hide?

Could we finish? Could we finish,

triple pretty please? Where did we hide

trapdoors so nobody would trip

through and snap necks, or trip

wires that triggered more and more

difficult riddles about the before?

What had two legs and pried?

What had none and knew the difference

between flies and flies? Did we mean

distance there? When we caught

that mosquito plague, who carried

the bug from mouth to mouth?

Where did we learn how to gut

trout and bury entrails against tracking?

What if we thought what we learned

wrong? Among 101 uses for urine,

how many worked as antidotes to lies?

Did we mean fertilize or sterilize?

If we always followed the river,

how come we walked on the same graves

over and over and over? Who lived

in those caves, and how long was this

long pig? Which way was west

when fog clung in the pissingest wind?

What poison smog hung like a cross

between gasoline and jasmine

in our lungs? Did we mean minds?

Who said you forget as a threat

and made us cry? What got in our eyes?

Why was the sky ashy whitish?

Could we repeat the question?

Could we? Why? Why?

Why? Why?

No?

Steven D. Schroeder’s second book, The Royal Nonesuch (Spark Wheel Press, 2013), won the 2014 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award from Southern Illinois University. His poetry is recently available or forthcoming from Crab Orchard Review, burntdistrict, and Vinyl. He serves as co-curator for Observable Readings in St. Louis and works as a Certified Professional Résumé Writer.

Q&A

Q: If you would, talk a bit about word magic – your poems crackle with it, lively as Rumplestiltskin.

A: Wordplay and sonic effects come into my poems naturally in any case, and it’s particularly important for these poems. Throughout the series, language is treated as a means to power, a tangible object, and a sentient character, sometimes all at once. I also appreciate your mention of Rumplestiltskin, because he really was a nasty little piece of work, wasn’t he?

Q: Paper or screen? Pen or pencil or stylus?

A: Brain to paper to screen is common for the scraps I write down in notebooks here and there, often as I drift into and out of sleep. Paper to brain to screen happens during revision. In any case, voice needs to be an integral part of the process well before the completion of the poem. If I am not reading the poem aloud to myself as part of drafting, it’s not going to work out.

Q: Can we still have the same relationship with the dictionary that we had before the OED and Webster's went online?

A: Well, it’s even easier to look up dirty phrases with Urban Dictionary, so I’d say so. Personally, I still have a gigantic old Merriam-Webster hardcover that I bought over a decade ago, but I don’t think it’ll go with me the next time I move.

Q: The line in “The Book” that “they locked it/in a glass case and cracked/our glasses” brought an immediate image of the classic “Twilight Zone” episode “Time Enough at Last.” Were you a TZ fan, and if so, what episodes haunt your dreams?

A: I was definitely thinking about that episode when I wrote those lines, though in this case of course there’s an oppressive external force doing the breaking. The series was before my time, so I know it more as archetypes: the one person who sees the threat, the strangers who aren’t what they seem, the fraught choice with ironic consequences, etc. I love turning tropes like that to my own ends.

4 Prose Poems by M.E. Silverman

Followed by Q&A

Response to: Step on a Crack

Every kid knew the legends, how Jimmy’s Mama said she slid on ice, her legs scooped skyward, defying gravity, until thud & shriek, her bones slipping out of place, her back broken. Hard to say anything about the shiner. Put the blame on Jimmy, they taunted, step on a crack, break your Mama’s back. Father finger pointed to Jimmy, but clipboards kept coming, forms needed filling, boxes required checking. Father rode in a red-wailing car. The world felt surreal & nothing seemed the same. Worse, the rest of summer turned lame. Kids stopped playing on their side of the block. Grandma came over a lot more, while Mama moved slow-slow in her chair, that she painted tortoise-green, moving-green, new-room green. Out in the woods, cousin Judy made him cry, claiming his Father would never come back before she twirled & sang in falsetto

Jimmy steps on a crack, breaks his Mama’s back.

His Daddy hit her because he’s a little shitter.

This made his cheeks hot & he wanted to pop her in the mouth to shut that trap. It was Grandma who set him straight later that night after the bedtime ritual of reading. She was in the middle of a fairy tale, something about a forest and being lost. His mind drifted, waiting to ask about the earlier event. Oh, Jimmy, those are just folks telling tales. Not long ago, we thought the number of cracks meant the number of china dishes we would break before the sun set. He didn’t really know this “superstition”; sounded like someone patching up a large hole or hemming up new pants with Mama’s super stitchin’. Restless, he dreamed about snow & sharp shards. At his new school, his teacher with the name that sounded close to old-bird warned if kids stepped on the cracks in the street, they would get eaten by bears waiting around corners for a small snack to walk by & the thought of Judy being devoured by three bears made him feel just right inside.

Response to: Don’t Swallow your Gum or It will Grow into a Tree

For once, Mama was right & the tummy tree took root, running through my sister’s body, a nightmarish version of Tai Chi as her internal energy developed during Zhan Zhuang into bark & trunk, twisting knots & squishing through softness, a slow, strangling snake ready to swallow the waste she’d become, twigs sprout from knuckles & break through her jail-ribs but ignore the leaking heart-sack as branches fatten & stretch skyward while leaves unfurl cocoons of foil-wrapped candy bars ready for the entire neighborhood’s savage consumption until they each bloom gum ball bone & dangle cotton-candy moss forever surrounding her chewed-up altar.

Response to: I Don’t Believe You

With two words, it happened jackrabbit fast, an idea darting under the shrub & away from the speeding light, swirling into the heavy distance, a spell cast, a cause deserted. I don’t believe you. I don’t believe you. She stared incredulous, wide-eyed, with one hand on her hip & her left hand opened, ready to stop something larger than this moment, the heart’s barrier, a dream catcher of flesh & bone & nail. I. Don’t. Believe. You. He listened the way a child presses an ear to a keyhole, carrying a sense of magic & the impossible into a room caught in darkness where some sound could mean mermaid, could mean dragon. He heard her. He heard the loose strand of hem, the eye lid’s extra blink, the let loose arrow a mile away. He heard in you. In you.

Response to: You’re Going to Dig a Hole to China

If you’re reading this, you know the whole incident is classified, can’t talk about it. Sealed lips, signed forms. The works. In fact, this is “fiction.” For the dog & my kid, well, let’s just say it’s a dream, the ones where you know you’re in a dream but you go with it anyway because waking up is more trouble & really you’re just still tired, more sick & tired. I should mention, sometimes the neighbors came over on Sunday afternoon when it was our day to fire up the BBQ, bring out the dogs & turn small talk into an art. The kids would all scramble about, an organized fire crew sliding up & down the embankment, enjoying the moment, making mountains out of molehills, literally. Listen, I know the newspapers need their story, had their fun at our expense, but honestly there was nothing better than standing on flagstone, flipping burgers, breaking out a twelve pack, & watching all the kids & a few fathers scurry meerkat-like, filled with determination & joy for the moment. Make no mistake, “nothing” happened. How did it end up, you ask? The way all memories do, muddled with those little pleasurable points in time, the ones where we remember reaching over to our significant other, one hand on a shoulder or caressing hair, faces full of smiles for our life together, when sex meant sharing not warfare, before the lawyers & their blue pens, before weekend events became caught in the shadows of work-long weekdays, before we dug ourselves out of that muddy cul-de-sac hole.

M. E. Silverman is founder of Blue Lyra Review and Review Editor of Museum of Americana. He is on the board of 32 Poems and is a reader for Spark Wheel Press. His chapbook, The Breath before Birds Fly (ELJ Press, 2013), is available. His poems have appeared in over 75 journals, including: Crab Orchard Review, 32 Poems, December, Chicago Quarterly Review, North Chicago Review, Hawai'i Pacific Review, Tupelo Quarterly, The Los Angeles Review, Tulane Review, Weave Magazine, and other magazines. He recently completed editing Bloomsbury’s Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry with Deborah Ager and is working on anthology about the body. http://www.mesilverman.com

Q&A

Q: The function of memory, personal and cultural, pervades these poems. What is your earliest memory?

A: My earliest memory is standing in front of a screen door watching the rain water rise and my mother scared and screaming about a flood. Perhaps that is why I often write about water and have a series of poems about a modern-day Noah?

Q: Paper or screen? Pen or pencil or stylus?

A: I have no idea exactly what this is referring to: reading or writing? I like to read on my tablet and keep all my books in one place so that I can read poetry or mystery or sci-fi or whatever I am in the mood for with one click. But I cannot write on such a small space. I need a bigger computer size screen. Sometimes I use pen and paper to write when waiting in the car for my daughter or when I don’t have access to the computer.

Q: The prose poem inhabits much the territory as the flash fiction. What are the field marks that can help us distinguish one from the other?

A: This is the exact question I have been wrestling with! Are my prose poems poems or stories? To be honest, I cannot distinguish the difference between flash and prose poems. But if one had to force me, I would say that flash fiction has more of the elements of fiction then a prose poem which relies more heavily on imagery and the elements of poetry.

Q: Words have power, words can do magic. This was true for most of human history – tell us how you came to address it as a contemporary phenomenon in these poems.

A: I think this is true. I am writing a series of poems about the last Jew in Afghanistan who stayed even after his family did not. This idea of extinction and longing and loneliness haunts my work. I think becoming aware of these things or other emotions could prevent us from experiencing them or if we have experienced them already, then writing can help one better understand what one went through.

The Blind Seer by James Alan Gill

Followed by Q&A

was about nine or ten years old when the faith-healers came to visit my grandfather. On a weekday. I remember that because, every day after school, I’d walk the streets of the tiny rural town where our family had lived since the mid 19th century to his house, where I’d stay until my mother got off from work. The healers entered the house with hushed voices, as if someone were sick or dying. I was watching cartoons on the television, but they invited me to join them at the table. “You know all too well the price of your grandfather’s blindness,” the man said to me, a small pity-filled smile on his lips. I nodded in agreement because it seemed the correct response.

The faith healers were one of a few young couples in our church who were trying to give evangelical Christianity a 1980’s hipness: guitar strumming praise teams, Christian rock concerts, and hand-raising zeal. The man had thinning permed hair, and I remember thinking he looked like a strange cross between Richard Simmons and Luke from General Hospital. The woman was unremarkably pretty, thin with dark brown hair. She was quiet through all of this. They had a young daughter, and thinking back now, they had to be very young themselves.

They had asked my grandfather if they could interview him for the church newsletter and pray for him. I don’t think they mentioned anything about their thinking they could work miracles.

A few Sundays before in church, the man stood in front of the congregation and told a story of how their daughter had been sick for two days, and they hadn’t known what to do for her, so they prayed over her bed, laid hands on her feverish skin, and according to the man, the little girl vomited up a green, stinking mess, and afterwards was made well.

Most parents know this situation well. Not the praying and laying on of hands, but a child puking and then suddenly feeling better. But this man saw it as something more, and he stood there at the pulpit, tears in his eyes, and said that the devil had made his little girl sick, and that the Lord cast out that evil spirit and made her well. I still remember clear as day my mom saying under her breath, “That ain’t no demon. Ain’t nothing but the terrible twos.”

But they were convinced that maybe they could do the same for my grandfather. That since their healing touch worked so well with their daughter, maybe, just maybe, they could restore sight to the blind.

The first question they asked my grandfather was about how he’d become blind, and how he’d learned to live with it so well. For the first twenty-six years of his life, he was like anyone else: graduated from high school in 1941, then went to the Army and fought in Europe. But it wasn’t the war that took his sight, though he’d seen combat in France and Germany, winning a bronze star along the way.

His blindness came a few years after he’d returned from overseas and had married and had my father. A tumor developed on his brain, and the doctors were able to remove it with surgery and spare his life, but in order to do so, they had to take the part of his brain that gave him sight. The last image Phillip had of my father was that of a two-year-old boy, toddling around the house.

After he had recovered from the surgery, he left his family in southern Illinois for a year to attend a school for the blind in Chicago, and there he learned how to get around rooms, buildings, streets; how to read and write Braille; how to live in the dark.

And he did it well. He walked around our small town without a cane. And even when he was older and his balance wasn’t always the best, he carried a black cane, because he said that without a white cane, many people didn’t even know he was blind, which sounds absurd, but anyone who knew my grandfather found it easy to forget, mostly because of his wood shop.

Everyday he would walk from the house to the old garage and work much of the day building furniture (even now, I have several pieces sitting in my house). The only special tools he used were squares and rulers with Braille numbers; everything else was straight from Sears. He even ran a table saw.

As a little kid, I would sit in the floor of the shop, the sweet smell of sawdust and fresh cut lumber in the air, playing with pieces of scrap that he kept in a pile in the corner. We would be talking and then Grandpa’d say, ‘Hold your ears’, and flip the switch to the saw, then he would push the wood carefully toward the spinning blade with his fingers, never once coming close to injury. I didn’t even consider this as something extraordinary. I knew that I wasn’t supposed to mess with the table saw because I might cut off my fingers, but I never once thought it odd that a blind man should be concerned.

The young faith-healer took furious notes in a spiral bound notebook, much like the ones I used in school. When he felt he had enough history, he asked my grandfather for his testimony. In our church, this was a regular part of worship service, usually on Wednesday nights. People would simply stand up and tell the story of how they been saved. In a small town like ours, there were never many new people moving in, and the congregation was pretty much the same as it had always been, so you learned people’s testimonies fairly quickly, and there was a uniqueness and beauty to the way each person told theirs. There was a rhythm and rhetoric that each individual brought with their oratory. But sitting there at my grandfather’s kitchen table, I realized that I’d never heard him give his. He was a quiet man in church services. There were plenty of others who couldn’t wait for their turn to take the stage, but when he spoke, it was usually striking and profound.

All the churches in our area loved to put on Christmas Plays and Passion Plays, and great effort was put into their productions: I once saw a man carry a life size wooden cross while wearing a crown of thorns made from Bradford Pear branches, the thorns actually drawing blood from his forehead; earlier in the play, he’d been whipped with a cat-of-nine-tails that had been soaked in fake blood so that with every stroke, his back became more and more covered in gore.

The Christmas Plays were much less violent, usually involving children as shepherds and angels, and wise men dressed in bathrobes and towel-turbans, looking more like they’d just had a shower.

In one of these Christmas plays, my Grandpa Phillip played Simeon. That year someone in the church had had a baby in the fall, so there was a real infant to play the Christ child, and I can still picture my grandfather taking the baby from its mother’s arms and holding in front of his dim eyes, saying “Lord, now let thy servant depart in peace, for mine eyes have seen thy salvation, a light to lighten all people.” And in that moment, you believed it. When you were with my grandfather, it was easy to have faith.

So now, for the first and only time, I heard him tell the story of how he’d come to that faith. Of course he’d been raised in church like most people in that time and place, but his young life wasn’t particularly righteous. The story Philip told of his conversion is a sort of Paul on the road to Damascus in reverse. It was in the mid 60's and he’d been blind for fifteen years at that point. By this time, his marriage had deteriorated and it was known by most that they were only staying together for their kids. They had a daughter eight years younger than my father, and gossip questioned whether she was even my grandfather’s, though I never heard anyone in my family speak of it. My dad had just graduated high school and gone into the service, destined for Vietnam.

During this time, Philip went to a church revival that was being held in the West Frankfort Illinois high school gym. He never said anything about the sermon, just that being in the hot gym, sitting in hard wooden folding chairs with the whisper of the women’s fans as they waved them back and forth, had been a comfort. All that human energy bound up in one place with the talk of faith and hope hovering over their heads. Then while the congregation was singing, he looked up, and as he told it, the darkness over his eyes washed away, and for about ten seconds, he could see the roof of that gym--the hanging lights, protected by wire screens; the iron girders criss-crossed under the curved roof; the giant black furnace, quiet and cold on that July night, suspended over center court--then the edges of vision blurred and darkened, closing in to a single point until there was nothing.

Not long after, he and my dad’s mother divorced. Maybe it was his failed marriage that drove him back to the church, the need for something to give meaning to what seemed a life gone wrong. Maybe he felt his blindness was a sort of punishment for backsliding. I never remember him saying as much, but things change over time; things once believed fall away, replaced by new interpretations. With each year, my grandfather continued to accept his life without sight, and by the time I knew him, any anger or bitterness that may have been there was no longer a burden to him. Saved by the grace of God, he would say.

Who knows what my memory of this day would have been if it would have stopped there. If this young couple would have thanked my grandfather for his time and taken their notebook and went to type up their article to be mimeographed and passed out at the church. Instead, the young healer pulled out a little glass bottle of oil (I’m not sure what kind it was; olive oil wasn’t common in rural southern Illinois back before everyone started dropping dead from heart attacks, so for all I know it could have been Wesson) and he dipped his finger, and said, “Phillip, I’m going to pray over you now,” and he rubbed the oil over my grandfather’s eyelids. Then he and his wife began to pray, standing on each side of the chair grandpa sat in, invoking the power of God to reach down and restore his sight, saying that miracles were real and not something of long ago, that scripture taught that the disciples of Jesus Christ were given his power to heal the sick and cast out demons through the Holy Spirit, and so now they commanded, “Reach down with your mighty hand, oh Lord, and touch the eyes of Phillip.”

And I prayed too. At first I simply watched and thought how strange it all looked, these grown people with their eyes crunched tight, touching the bald head of my grandpa above his patient face. But then I thought, wouldn’t it be great if he really could see again. He could come to my baseball games and see my dad all grown up and watch television instead of just listening. And then I thought, what if the only reason it won’t work is because I’m sitting here watching instead of praying. And so I prayed. I shut my eyes and I prayed at earnestly as I could. God, I said, if anyone deserves a miracle, it’s him.

I don’t know how long it was before they gave up. When I finally opened my eyes and saw them still there with faces strained with belief, I was embarrassed. Embarrassed for them and their snake oil religion, and embarrassed of myself for actually buying into it.

They did finally give up, and awkwardly shook hands with my grandfather and told him they’d continue to pray, that God works in mysterious ways, etcetera, and then they left. I sat waiting for my Grandpa to say something. I wondered if he was disappointed. I wondered if he had the same feelings I did, had been skeptical, then hopeful, then ashamed. I don’t know. He never spoke of it again. We just sat there in the quiet of his house, the clock ticking in the other room, and then he stood and put on his ball cap and went out to his wood shop, and I went back to my cartoons, as if we’d just been visited by people selling insurance or energy efficient windows.

James Alan Gill has published fiction, non-fiction, and poetry most recently in Colorado Review, Crab Orchard Review, Midwestern Gothic, Night Train, and Atticus Review, and has work forthcoming in the anthology Being: What Makes A Man. He is the Dispatches editor at The Common and currently lives in Eugene, OR.

Q&A

Q: What surprised you most during the process of composing and revising this piece?

A: The biggest surprise was how difficult it was to capture my grandfather. He was such an amazing and unique man, I found myself continually reworking the narrative in order to include as much detail as I could about him without sacrificing the forward movement of the story. I’m still not sure I succeeded.

Q: What’s the best writing advice you’ve received? Did you follow it? Why, or why not?

A: My mentor, Kent Haruf (who just recently passed away), wrote this to me once in a letter, and I continually go back to it to remind myself what is at stake when writing, that it isn’t a contest or a ladder of success to be climbed, but instead about something that transcends those things. He said, “It seems to me too that somehow someway you have to trust that if you will write at your deepest most personal level, most idiosyncratic level, at your most engaged level, writing what you yourself truly feel without regard to what anyone else says or has written before, believing in the truth and value of your own experience and feelings, then you have a chance—a chance—of writing something lasting.”

Q: What three to five authors and/or books have inspired your journey as a writer?

A: I have been inspired by so many writers, and continue to be inspired by new writers all the time. But the three that I’ve had the privilege to study with closely and to know as friends, the ones I would consider mentors, are the novelist Kent Haruf, the poet Rodney Jones, and the novelist Whitney Otto.

Q: Describe your writing space for us. Are you someone who finds the muse in a public space such as a café, or in a cave of one’s own?

A: This continually changes. I’ve written well in both public and private spaces. Lately, I’ve taken great enjoyment writing rough drafts on my 1950’s portable Underwood typewriter. When I first started writing, in elementary and high school, and then on into undergrad, I wrote on a typewriter not out of nostalgia but due to financial limitation: I longed for a computer. After years of writing on desktops and laptops, I’ve again found the visceral joy of pounding on keys and getting words on the page without concern for spelling or format or visual polish. Going back to correct or rewrite isn’t convenient, so one can only go forward, filling up the page with words and more words. Revision is done by hand, then the entire page typewritten again, then revised again, then typewritten once more before being put into the computer. It forces me to be deliberate and present in my process.

Three Secret Places by Kathleen Blackburn

Followed by Q&A

I.

Now, when I look back on that leaden summer of my father’s passing, I see the month of June as a partitioning of two existences, the before and after, the universe a landscape of abstractions fueled by grief and memory; but in 1998, when I was thirteen, the world was split, simply, between my parents’ white-brick ranch-style home and the ground beneath the branches of an overgrown peach tree in the alley. I discovered the peach tree when I was carrying out the trash one afternoon. Heat refracted off the metal bins. Flies buzzed above the waste and I turned to go back to my parents’ gate, back to the house where inside my father was crying for more Codeine, when I saw the tree branches, like a curtain at the edge of the alley, fill with breeze.

The leaves were brittle and thinned at the tips. Peaches hardened and fell to the ground too early, but to me everything about those branches was sacred and of paradise. I leaned against the fence and crossed my legs. I combed for peaches that hadn’t fallen yet but were ripe enough to eat. Some were light green blushing to yellow. I savored each bite, pressing the flesh to the roof of my mouth with my tongue. My mouth watered.

I went back as often as I could. Maybe three times a week. The shade was cool and dark brown between the neighbors’ fence and the tree limbs, which brushed the dirt floor. I waited for birds and white butterflies. Black ants marched across my sandals. I spied on the neighbors driving by on Raleigh Avenue: the Johnsons’ Chevrolet Suburban, the Laceys’ Toyota 4Runner that smelled like pot, which my dad had told me was a worse kind of cigarette. I felt to see if the hard knots of my breasts felt bigger. They did, and less painful. To preserve my peach tree spot, I planted the leftover seeds. I imagined an enormous peach tree blooming at the edge of the alley on Raleigh Avenue with peaches like gold bells tucked away in the boughs. I pictured it thriving as few trees in West Texas do, flowering like a lavish bouquet in spring, the petals drifting down the streets like snow. And no one would know, I thought, in the years to come, after everything else that will have happened in the world, that I planted the magical peach tree at the edge of Raleigh Avenue.

I can’t speak for other children. I know the desire to imagine other worlds, alternate realities, is common. I obviously don’t know what my life would have been like had I not, at 13, had a father who was dying of fourth-stage colon cancer inside my parents’ house. Perhaps I would have imagined something more fanciful than another peach tree in the alley. Something with centaurs or dragons. Something altogether separate from this life; not of a tree rooted to the earth next to the dumpster in the alley, right by the fence that my father built. Between the posts I could see the empty yellow swings of the swing set he also built. He moved that swing set to three different houses before he died, each time untwisting then twisting back into the earth the twelve-inch ground anchors he used to secure each pole. I peeked through the peach tree limbs and saw the windows of our house. They were dark for how bright it was outside.

I didn’t stay long behind those branches. My mother would have come looking for me and anyone’s discovery would have ruined the whole thing. The ground there was secret and I became secret when there. I disappeared into the peach blossoms. The supine leaves.

Days, or perhaps weeks, after my father died, the neighbors cut the peach tree. I’ve lost count.

II.

In the fall of 2011, when I was twenty-six and had, temporarily, given up drinking so much whiskey, I moved into a small house in Columbus, Ohio, two blocks west of active train tracks. I used to take walks in the evening, as the air dried to winter, and watch the train. It ran north/south, parallel to High Street, Columbus’s main thoroughfare. I’d been told once, by a soft-spoken and kind Midwestern man, that High Street was the spine of the city, and have, in the years since – during which I’ve taken up whiskey again, returned to my hometown of Lubbock, Texas, where I was found stumbling through the parking lot of a lawnmower shop called “Paul’s Parts”, by a policeman who said that the only thing that really breaks in a person is the heart – imagined that cities are lithe, scaly vertebrates sleeping on their bellies.